Chapter 4: Organization of the Ordnance Department: 1940–45

The Early Months of 1940

In the early months of 1940 the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington was still housed in the Munitions Building, which had been its home since World War I. General Wesson’s staff at the end of May numbered 400-56 Regular Army officers, 3 Reserve officers, and 341 civilians.1 All the other supply services also had their headquarters in the Munitions Building, and overcrowding was becoming a serious problem. By the end of the summer the Ordnance Department had outgrown its peacetime quarters and in December moved to larger, more modern offices in the Social Security Building on Independence Avenue.

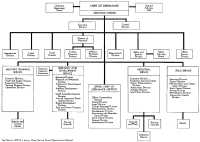

No essential change in the Ordnance mission or organizational pattern had been made for nearly twenty years, but the complexity and variety of the Army’s weapons had increased and by 1940 plans were well under way for their production in enormous quantities. With $176,000,000 allotted to the Department for the fiscal year 1940, and many times that amount for the following year, the procurement and distribution of munitions was becoming “big business.” General Wesson’s staff in 1940 was divided, as it had been since 1920, into four main groups—the General Office, the Technical Staff, the Industrial Service, and the Field Service.2 (Chart 1) The General Office performed administrative duties under direction of the executive officer, Brig. Gen. Hugh C. Minton. The Technical Staff supervised tests of experimental equipment and collaborated, through the Ordnance Committee, with the using arms. The two main operating units of the Ordnance office were the Industrial Service, with broad responsibility for production and procurement, and the Field Service, which handled supply.

To aid in administering the Department, the Chief of Ordnance was authorized by law to have two assistants with the rank of brigadier general.3 During General Wesson’s term of office the assistants were Brig. Gen. Earl McFarland and General Harris. In 1940 General McFarland was chief of the Military Service, with jurisdiction over both the Field Service and the

Chart 1: Organization of the Ordnance Department: 31 July 1939

Maj. Gen. Charles M. Wesson, Chief of Ordnance, 1938–42

Technical Staff, while General Harris was chief of the Industrial Service. This arrangement gave emphasis to the distinction between the military duties of the Chief of Ordnance, for which he was responsible to the Chief of Staff of the Army, and his industrial duties, for which he was responsible to the Assistant Secretary of War.

By far the largest of the four groups was the Industrial Service which, in addition to its procurement and production functions, had responsibility for designing and developing new and improved weapons, since Ordnance at the time had no Research and Development Division.4 During the spring of 1940, when interest in the rearmament program was growing, Col. Gladeon M, Barnes, chief of the Technical Staff, urged General Wesson to separate the research function from production and procurement by establishing a research division independent of the Industrial Service, Colonel Barnes argued that this would give the research experts freedom to carry on their investigations and experiments without being constantly hampered by production problems.5 But General Wesson decided that the most pressing need at the moment was not for more time-consuming research and experimentation with new weapons but for the preparation of blueprints and specifications for equipment already approved. He chose to keep design and development within the Industrial Service and, at the same time, to strengthen that service by adding three experienced officers as assistants to General Harris. He named Col. Burton 0. Lewis as assistant chief for, production and procurement; transferred Colonel Barnes from the Technical Staff to the Industrial Service as assistant chief for engineering; and a short time later ordered Lt. Col. Levin H. Campbell, Jr., from Frankford Arsenal to Washington to become assistant chief for facilities.6

These three “vice presidents,” as they were familiarly known in the Department, assumed their duties while Ordnance was being tooled up for the big job ahead. In the summer of 1940 the Industrial Service was suddenly called upon to negotiate contracts amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars for a great variety of complex

Chart 2: Organization of the Industrial Service

Supersedes old tracing 16-23-215, under revision date, July 24, 1941

weapons. The district offices were expanding their small peacetime organizations as quickly as possible and were preparing to handle procurement assignments on a grand scale. The three assistant chiefs aided General Harris in exercising effective supervision over the operating divisions of the Industrial Service during this period of rapid growth.

Management of supply activities was the responsibility of Field Service. It stored and issued matériel; inspected, repaired, and maintained ordnance equipment, whether in storage or in the hands of troops; and administered storage depots, renovation plants, and other field establishments. The growing importance of supply operations early in 1940 led to the assignment of the executive officer for Field Service, Col. James K. Crain, as chief of the Field Service, under the supervision of General McFarland, chief of the Military Service.7 The Field Service at that time was organized into an Executive Division, a War Plans and Training Division (later renamed Military Organization and Publications Division), and three operating divisions—Ammunition Supply, General Supply, and Maintenance. In April the Maintenance and General Supply Divisions were placed under the direction of Col. Everett S. Hughes, then designated chief of the Equipment Division, to bring about closer coordination of their activities, particularly as they concerned spare parts,8 Under Colonel Crain’s supervision, specially trained Ordnance companies and battalions were organized to administer Field Service depots and maintain Ordnance equipment in the hands of troops. Construction of new storage facilities was begun during 1940, and in midsummer the Field Service handled its first big prewar assignment—the transfer of over 50,000 tons of Ordnance supplies to the British Army.

From the Office, Chief of Ordnance, control was exercised over an increasing number of field establishments. These were divided into four main groups, with the General Office administering the schools, the Technical Staff the laboratories and proving grounds, the Industrial Service the arsenals and district offices, and the Field Service the storage depots and renovation plants. General Wesson delegated full authority to the commanding officers to carry on day-to-day operations, subject only to broad policies determined by the Washington headquarters. This practice was based on the traditional Ordnance policy of “centralized control from the Washington office with operations decentralized to field agencies.9

At General Wesson’s 11 o’clock conferences, held virtually every day, members of the staff reported on progress and difficulties and threshed out common problems. Sometimes only two or three officers attended and at other times the heads of all the groups and staff branches were present. On several occasions the Chief of Staff and other representatives of the War Department high command attended. Under General Wesson’s leadership, the “11 o’clocks” served as the central policy-making agency for the Ordnance Department.10

Organizational Developments, June 1940 to June 1942

Most of the changes in the organization of the Department between June 1940 and June 1942 resulted from the swift expansion of Ordnance operations, beginning with the Munitions Program of 30 June 1940 and culminating in the multibillion-dollar arms appropriations of early 1942. The extent of this expansion is indicated by the rise in the number of people in the Washington office—from 400 in May 1940 to 5,000 in June 1942. Between these two dates nearly 100,000 civilian workers throughout the nation were added to the Ordnance Department payroll, not counting hundreds of thousands employed by contractors holding Ordnance contracts.

In spite of this rapid growth, few changes were made in the organization of the Department until June 1942 when Maj. Gen, Levin H. Campbell, Jr., became Chief of Ordnance, General Wesson’s hope, expressed in early 1940, that “the machine is so designed and planned that it can meet the load imposed on it without breaking down,” was largely realized.11 The changes in the headquarters organization were mostly additions to the staff, such as the establishment of a Lend-Lease Section in the Fiscal Division after the passage of the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941. Similarly, because of the pressure for increased tank production in the spring of 1941, a separate Tank and Combat Vehicle Division was split off from the Artillery Division of the Industrial Service.12

In July 1941 General Wesson made one major organizational change when he abolished the Technical Staff and transferred its functions and personnel to various branches of the Industrial Service.13 He assigned most of the former Technical Staff functions to Brig. Gen, Gladeon M. Barnes, who then became the assistant chief for research and engineering in the Industrial Service. General Wesson’s purpose was to eliminate duplication of effort between the Technical Staff and the Industrial Service. This change, coupled with the increasing independence of the Field Service under the leadership of Brig. Gen. James K. Crain, led to dropping the position of chief of the Military Service in the summer of 1941. General McFarland, who had filled this position since 1938, was assigned to continue as chairman of the Ordnance Committee and to supervise and investigate various activities pertaining directly to the Office, Chief of Ordnance.14

A fourth “vice president” was added to the Industrial Service in July 1941, when Brig. Gen. Richard H. Somers, former chief of the Technical Staff, was appointed assistant chief for inspection.15 General Somers was responsible for testing new matériel at Ordnance proving grounds and for coordinating all inspection activities within the Industrial Service. As the munitions production curve began to rise, and as plans for a tremendous procurement program matured, inspection assumed huge proportions.

In December 1941, a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Brig. Gen. Burton 0. Lewis, assistant chief for production and procurement, was named deputy chief to General Harris. General Lewis’

Chart 3: Organization Of The Ordnance Department: 1 February 1942

responsibility for supervising production was then taken over by General Campbell, who had virtually completed his earlier assignment by getting the construction of new facilities well under way.16 At the same time, the Department’s procurement program was turned over to Colonel Quinton, former chief of the District Control Division, who became assistant chief for purchasing. In this capacity Colonel Quinton supervised the purchasing activities of the arsenals and Ordnance districts and maintained liaison with the Office of the Under Secretary of War and the Office of Production Management.17

In the Field Service several organizational changes occurred during 1941 and early 1942. The first was the establishment in July 1941 of the Utilities Division, which was to plan the construction of new storage depots and provide for maintenance and new construction at all existing Ordnance depots.18 By the spring of 1942, Field Service exercised control over forty-two field installations as compared with twenty-seven two years earlier. Fifteen new depots for the storage of ammunition and other ordnance supplies had been built, and the Wingate Depot in New Mexico had been so extensively rebuilt that it was practically a new installation.19

In February 1942 a whole new level of administration was added to the Field Service when six positions of assistant chief, roughly comparable to those of the assistant chiefs of the Industrial Service, were created. By then the volume of business in the Field Service had become so great that General Crain felt it essential to have the assistance of experienced officers capable of assuming a large measure of responsibility.20 Each assistant chief was made responsible for a phase of Field Service activities in which he was specially qualified, and was required to report directly to the chief of the Field Service. Col. Charles M. Steese was assigned plans and statistics, and ammunition and bombs; Colonel Hughes, artillery; Col. Morris K. Barroll, automotive equipment and armament; Col. Stephen MacGregor, small arms; and Col. James L. Hatcher, aircraft armament. The new appointees also maintained close contact with the appropriate assistant chiefs of the Industrial Service in order to expedite deliveries of ordnance from factory to training center or fighting front.21

Relations with Army Service Forces

The 9 March 1942 reorganization of the Army brought about a fundamental change in the relationship between the Ordnance Department and higher headquarters.22 With the establishment of the Services of Supply, the Army Ground Forces, and the Army Air Forces, a new level of command was placed between the Ordnance Department and the Chief of Staff and Under Secretary of War. The

commanding general of the Services of Supply, Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, was given broad powers over all the supply services.23 He and his staff not only took a large part of the administrative burden off the shoulders of General Marshall and Under Secretary Patterson, but also worked out the Army Supply Program to guide procurement activities of the supply services.

The new headquarters combined in one organization all elements of supervision formerly divided between G-4 of the General Staff and the Office of the Under Secretary of War. The March 1942 reorganization did not abolish the Office, Chief of Ordnance, or the offices of any of the other supply chiefs as it abolished the offices of the Chiefs of Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery, and Coast Artillery when those arms were united to form the Army Ground Forces. As a result each supply service continued to have some measure of independence. The Ordnance Department, for one, vigorously resisted further moves to limit its prerogatives and to interfere with its methods of operation.

In the relations between Ordnance and ASF friction gradually developed and eventually increased to such a degree that it had a marked effect upon the functioning of the two organizations.24 The Ordnance Department, with its century-old tradition of independence and technical competence, looked upon the new headquarters with suspicion and resentment, while a few of the officers in ASF considered the Ordnance Department rather stiff-necked and imbued with an uncooperative spirit bordering at times on insubordination. Some ASF officers regarded Ordnance not only as being too conservative and unimaginative but also as being so intent upon protecting its own interests that it sometimes placed them above the interests of the Army as a whole.25 Col. Clinton F. Robinson, director of the ASF Control Division, commented in April 1942:

There appears to be a decided fraternity or clique feeling among the majority of Ordnance officers. . , . There is apparently a belief that there is something “mysterious” about the design and production of Ordnance munitions; Ordnance officers are specialists in this—no one else knows anything about it, and no one should interfere. Apparently there is the feeling that the way the organization should operate is to give the Ordnance Department the job, and complete authority for production of Ordnance munitions, and then for any higher headquarters to forget about it and assume that the job is being done. ...”26

Ordnance officers believed that there was a great deal about the production and maintenance of munitions that the uninitiated could not readily comprehend, and many who had specialized in their chosen fields for years resented supervision by officers on General Somervell’s staff who

Chart 4: Ordnance in the Organization of the Army: 1942–45

were not familiar with the nature of Ordnance problems. They complained that they were forced again and again to waste valuable time explaining to a succession of ASF officers why existing Ordnance procedures were necessary, why munitions production “could not be turned on and off like a water spigot,” and why proposals for achieving greater efficiency would not work. One top-ranking Ordnance officer summarized the Department’s point of view:

The Ordnance Department had been a procuring service over a period of some 130 years. During that time it had developed a certain know-how concerning procurement and manufacture. Very few of the members of the ASF headquarters had any experience in the procurement or manufacture of ordnance items. ... There was a group of some two or three thousand in the ASF headquarters with little or no experience along our specialized line who were continually telling us just how to do our job in the minutest details. We resented this, and I think rightly so.27

The Ordnance Department fully recognized the need for control of the Army’s procurement program by an agency such as the General Staff, the Office of the Under Secretary of War, or the ASF, but it strongly objected to attempts by any such agency to take on direct operating functions or to supervise its activities too closely. As General Harris once expressed it, “The higher headquarters should chart the course, but not keep a hand on the wheel.” In accord with this policy, the Ordnance Department, during 1941 and early 1942 when it was directly responsible to the Under Secretary of War, had arranged frequent production conferences to which Mr. Patterson, members of the General Staff, and representatives of the civilian production control agencies were invited. “At these meetings,” said General Lewis, “the Ordnance Department took the initiative in laying its cards on the table. We said to Judge Patterson and to all the others present, ‘Here is what we are doing, and here is what we plan to do. Look over our production schedules and our program for the future and tell us if we are on the right track.’ These conferences, carried on in a spirit of cooperation and mutual confidence, promoted understanding, but were discontinued soon after the creation of the ASF.28

The new headquarters introduced impersonal supervision and reporting. In its efforts to harness the supply services and to keep them all pulling in the same direction at the same speed, it standardized procedures wherever possible and minimized the differences among the services. At the same time, the ASF staff exercised much closer supervision over the services than had the Under Secretary of War. Inspections of various activities and requests for statistical reports on many phases of the supply program became the order of the day and, as time went on, Ordnance officers felt that ASF interfered more and more in the details of Ordnance operations.

General Somervell recognized in the summer of 1942 that some members of his staff had gone too far. At a conference of the commanding generals of the Service Commands in August, he declared: “I know that you have been plagued with a lot of parachute jumpers from Washington. They drop in on you every day, in great numbers, and inspect you from hell to breakfast. We want to cut that out to a very considerable extent. I notice that here

in Chicago alone, for example, in the Ordnance District office, one month they had 151 inspectors come here ... 151. Well, how in the world they ever had a chance to do anything, I don’t know.”29 These comments suggest that many of the difficulties that arose in Ordnance-ASF relations could have been avoided if supervision by ASF had been more effectively coordinated and controlled. Particularly during 1942, while ASF was building up its organization and working out its internal plans of operation, friction frequently occurred as a result of inexpert implementation of ASF policies.

Other difficulties in Ordnance-ASF relations stemmed from the fact that in 1942 and 1943 only one high-ranking Ordnance officer, General Minton, held an important position in the ASF. The lack of Ordnance representation within ASF was due in large part to General Campbell’s reluctance to release badly needed Ordnance officers, but it nevertheless aggravated the Ordnance Department’s irritation over close staff supervision, and made difficult the development of mutual confidence. Many Ordnance officers agreed with General Somervell’s objectives, but they felt that ASF staff officers were defeating their own ends and delaying the Ordnance program by issuing directives that took little account of the Department’s problems. The presence of even two or three Ordnance officers in the councils of the ASF in 1942 might have served the dual purpose of allaying the resentment aroused by the very existence of the new headquarters and of adjusting ASF policies to fit Ordnance needs.30

Underlying the structure of Ordnance-ASF relations was the fear, shared in varying degrees by all the technical services, that the ultimate objective of ASF was to abolish the technical services. They feared they might some day meet the fate of the combat arms, which lost their identities at the creation of the AGF. General Somervell never reassured them on this point, and throughout the war the services saw the ASF as a constant threat to their independent existence. This feeling became particularly strong after a detailed ASF plan for abolishing the services was actually made public in the summer of 1943.31

Upon the Department’s internal organization also, ASF had important effects. Though ASF policy was to leave the commanding general of each technical service free to organize his own command as he saw fit, ASF in the course of the war directed a number of specific changes in the organization of the Ordnance Department. Moreover, the mere existence of ASF exerted an indirect effect on Ordnance organization. After General Somervell’s headquarters achieved a relatively stable organization, it urged the technical services to copy its pattern so that each ASF staff division would have a counterpart in each technical service. At the same time, the chiefs of the technical services were required to conform to certain broad principles set forth in the ASF Control

Manual and the ASF Organization Manual, and to submit all proposals for major organizational changes to the ASF Control Division for approval.32

The Latter Half of 1942

On 1 April 1942 President Roosevelt sent the name of Maj. Gen, James H. Burns to the Senate for confirmation as Chief of Ordnance to succeed General Wesson, whose term of office was to expire in June.33 General Burns, at that time executive officer to Mr. Harry L. Hopkins, chairman of the Munitions Assignments Board, was an outstanding Ordnance officer with a distinguished record. His nomination was promptly confirmed.34 But on 20 May the President nominated General Campbell to be Chief of Ordnance, explaining that General Burns had declined to accept the nomination.35 On the same day the War Department announced that General Burns had acted at the request of Mr. Hopkins who felt that an “urgent necessity” existed for General Burns to continue his work with the Munitions Assignments Board.36 In the summer of 1949 General Burns stated that he requested withdrawal of his nomination primarily because it had become apparent to him that the differences between his and General Somervell’s views on the management of the Ordnance Department were too sharp to be reconciled,37 On the morning of 1 June General Campbell took the oath of office in the new Pentagon Building, into which the Department—the first war agency to occupy quarters in the still unfinished structure—had moved a few weeks earlier.38

General Campbell had graduated from the United States Naval Academy in June 1909, and shortly thereafter resigned to enter industry. He was commissioned in the Army as a second lieutenant, Coast Artillery Corps, in December 1911. During World War I, while assigned to the Office, Chief of Ordnance, he worked on the engineering development of railway gun mounts. He served at various Ordnance installations during the 1920s and 1930s, devoting his attention primarily to the production of artillery, tanks, and ammunition. In 1939 and 1940 he won wide recognition for his success in introducing new automatic machinery for the assembly-line production of artillery ammunition at Frankford Arsenal. After being ordered to Washington in June 1940 to become assistant chief of the Industrial Service for facilities, he planned and supervised the construction of new plants needed by the Industrial Service and then succeeded General Lewis as assistant chief of the Industrial Service for production.

Lt. Gen. Levin H. Campbell, Jr., Chief of Ordnance, 1942–46

Immediately after General Campbell became Chief of Ordnance, the Department experienced more changes in organization and personnel than it had known during the preceding two and a half years. In the summer of 1942 there was not only the reshuffling of key men that normally accompanies a change in command, but also a series of changes in the structure of the Department. General Campbell, an energetic administrator, became Chief of Ordnance just as the full influence of the newly formed ASF was being felt and the Department was reaching the peak of its expansion.

The two most important organizational changes were the formation of new divisions in the Washington office and the further decentralization of the Department’s operations to field offices. General Campbell immediately created three new divisions—Military Training, Technical, and Parts Control—and placed them on the same administrative level as the Industrial Service and the Field Service.39 He changed the internal organization of the two latter divisions by abolishing the positions of assistant chiefs and decentralized the Department’s operations by establishing the Office of Field Director of Ammunition Plants at St. Louis, seven Field Service zone headquarters, the Tank-Automotive Center in Detroit, and other suboffices in the field.

General Campbell also appointed a special advisory staff of four prominent businessmen to consult with him on problems of industrial production. The members of this staff were Bernard Baruch, chairman of the War Industries Board during the first World War; K. T. Keller, president of the Chrysler Corporation; Benjamin F, Fairless, president of US Steel Corporation; and Lewis H. Brown, president of the Johns-Manville Corporation. The creation of this staff, General Campbell wrote at the end of the war, “was intended to underscore again and to reaffirm in the most emphatic way the tremendous importance of Industry’s role in the great, bewildering, onrushing armament program.40 Contrary to Campbell’s wishes, however, the two statutory positions of assistant chief of Ordnance were virtually abolished for the duration of the war by ASF headquarters in May 1942,

Chart 5: Organization of the Ordnance Department: 1 September 1942

When their terms expired at the end of that month, Generals Harris and McFarland were transferred to other duties.41

In addition to these organizational changes, General Campbell ordered the reassignment of nearly all the top-ranking officers within the Department headquarters. To an increasing degree, authority was delegated directly from the Chief of Ordnance to the heads of the operating divisions, and control of all these divisions was placed in new hands, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Hayes, an officer of outstanding production ability and experience who had served in the Office of the Under Secretary of War. during 1941 and then briefly as chief of the Production Branch of ASF headquarters, succeeded General Harris as chief of the Industrial Division. Col. Harry R. Kutz, who had served as chief of the Fiscal Division since 1938, was promoted to the rank of brigadier general and appointed chief of the Field Service Division, succeeding General. Crain. General Barnes, who had served for two years as assistant chief for research and engineering in the Industrial Service, became chief of the newly formed Technical Division. Of the other two new divisions, the Military Training Division was headed by Brig. Gen. Julian S. Hatcher, former commanding general of the Ordnance Training Center at Aberdeen, and the Parts Control Division by Brig. Gen. Rolland W. Case, former commanding general of Aberdeen Proving Ground.

This brief summary suggests that the changes made during the first few weeks of General Campbell’s term were so numerous and far reaching as to be almost revolutionary. The changes in personnel were indeed almost revolutionary, but the structural changes were less radical than they at first appeared. Most were the end products of a long evolutionary development. To persons intimately acquainted with the gradual unfolding of the Ordnance program for war production, they came as no surprise. General Campbell even felt that “reorganization” was too strong a word to use in describing the steps taken during his first few weeks in office, and preferred to say that it was simply a matter of “making additions to the organization,”42

Abolition of Assistant Chiefs of Industrial Service

The evolutionary character of the events of June 1942 is well illustrated by the abolition of the positions of assistant chief that had been created in the Industrial Service in 1940. This apparently sudden and drastic step was actually the culmination of a gradual development. In the fall of 1941, when General Campbell was serving as assistant chief for facilities, he had seen the need for his services decline as the job of constructing new manufacturing and loading plants got well under way. In December this position was abolished, on Campbell’s own recommendation, when he was appointed assistant chief for production. A short time later General Campbell concluded that the need for this position had also lessened because the operating divisions of the Industrial Service had succeeded in building up competent staffs and were able to manage their jobs without the supervision of an assistant chief. Substantially the same was true of Colonel Quinton’s duties as

assistant chief for purchasing and General Somers’ duties as assistant chief for inspection.43

The decisive factor that brought the “Assistant Chiefs Era” to an end was General Campbell’s conviction—shared by General Hayes, the new chief of the Industrial Division—that the positions of assistant chief violated fundamental principles of sound organization. “I did not want in the organization any ‘Vice Presidents’—men who were without real authority and responsibility,” General Campbell wrote, “I wanted the organization to be one of direct responsibility. If performance was lacking, then I could accurately and quickly assess responsibility for non-performance.”44

After the elimination of the assistant chiefs, a Production Service Branch was formed to absorb the remaining functions of the assistant chief for production and, later on, to assume responsibility for administration of the Controlled Materials Plan for the Department.45 The remaining functions of the assistant chief for purchasing were taken over by the various staff branches, particularly by the Legal Branch. Supervision of inspection activities was assigned to inspection sections within the operating branches of the Industrial Division, and these branches were placed on the same organizational level as the production and engineering sections to guard against the danger that quality would be sacrificed to achieve quantity production.

Field Service Division

The Field Service Division also experienced an organizational overhauling during June and July of 1942. General Campbell ended the six-months-old experiment with the assistant chiefs of the Field Service and eliminated two of the divisions that had been created during the preceding two years—the Military Organization and Publications Division, which became a part of the Executive Branch, and the Bomb Disposal Division, which was combined with the Ammunition Supply Branch. The number of main divisions of the service was thus reduced to five an Executive Branch, a newly created Plans and Operations Branch, and the three operating branches, Ammunition Supply, General Supply, and Maintenance.46

This reshuffling of responsibility occurred to a large extent because the new Plans and Operations Branch took over depot administration and other overhead duties affecting more than one branch. It absorbed the responsibilities and personnel formerly assigned to the Transportation and Facilities Divisions and consolidated them with duties that had been performed by the assistant chief for plans and statistics, Colonel Steese, who became chief of the new branch. In this way, all phases of depot administration including the construction and maintenance of buildings, the supervision of personnel, the control of shipments to and from the depots, and the gathering of statistics on available stocks were coordinated through a single staff branch.47

Military Training Division

Because of the rapid expansion of the Ordnance training mission, General Campbell established a separate Military Training Division in June 1942. Since enactment of the Selective Service Act in September 1940, the Department had been called upon to train an ever increasing number of officers and enlisted men at the Ordnance school at Aberdeen Proving Ground. Two additional training organizations were established at Aberdeen to carry on a well-rounded program—the Ordnance Replacement Training Center and the Ordnance Unit Training Center. To administer the three training units, and to supervise the training of military personnel at various civilian institutions, the Ordnance Training Center had been formed on New Year’s Day, 1941, with headquarters at Aberdeen,48 In establishing the Military Training Division, General Campbell converted the Ordnance Training Center into a full-fledged division on a par with the Industrial, Field Service, and other divisions of the headquarters,49 To avoid any break in the continuity of command, the Military Training Division was placed under the direction of the former chief of the Ordnance Training Center, General Hatcher. The organization of the new division was patterned closely after that of the training directorate at ASF headquarters.

Unlike the other divisions in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, all of which had their headquarters in the Pentagon, the Military Training Division at first had its headquarters at Aberdeen Proving Ground, where most of the training was carried on. To maintain contact with the other divisions of the Department and with ASF headquarters, a Liaison Branch was established in Washington. Placing the Military Training Division headquarters at Aberdeen was the first major attempt to decentralize the Ordnance Department, but it proved unsuccessful and it was abandoned within a few weeks. It soon became apparent, for example, that the large volume of directives and requests for information from ASF could never be handled fast enough through the Liaison Branch to satisfy ASF headquarters. The announcement in July that the Quartermaster Motor Transport Service was soon to be transferred to the Ordnance Department, along with a large-scale training program for automotive mechanics, further complicated the situation. The training section of the Motor Transport Service was in Washington—as, in fact, were the training sections of all the other supply services—and its schools were widely scattered. In mid-August General Campbell therefore ordered the Military Training Division to move its headquarters to the Pentagon. From that vantage point it directed the training of thousands of officers and enlisted men at training centers in all parts of the country.50

Parts Control Division

The importance of administrative machinery for handling matters relating to spare parts had been recognized early in the defense period by the Ordnance Department. In November 1940 General Wesson had appointed a permanent board of officers to determine the types and

quantities of spare parts to be ordered when large-scale production contracts were let.51 The board consisted of the chiefs of the Field Service. the Fiscal Division, the War Plans Division, and the assistant chief of Industrial Service for engineering. Within the various subdivisions of Field Service and Industrial Service spare parts sections were created to maintain lists of essential spare parts, arrange for the distribution of parts among the depots, and generally supervise spare-parts production and procurement.

Toward the end of 1941 it became apparent that this arrangement had not yielded altogether satisfactory results. By the very nature of their activities, the Industrial and Field Services were constantly at loggerheads on the subject of spare parts. The primary concern of the Industrial Service was to produce completed items of equipment, and it was under constant pressure from higher headquarters to get maximum production. The primary concern of the Field Service, on the other hand, was to build up stocks of replacement parts for maintenance work in the field. Any reconciliation of these two missions involved compromise, and there was no recognized objective standard of spare-parts requirements on which to base such a compromise.52 The problem finally became so serious that the Control Division of ASF headquarters made a special study of it, and the Ordnance Department on its own initiative called in experts from the General Motors Overseas Operations to investigate the matter and make recommendations.53 The reports of both groups emphasized the inadequacy of the coordination effected by the Sparc Parts Board and the various spare parts sections. “The major problem,” the ASF Control Division reported, “is that ten separate offices deal with various aspects of Spare Parts, and no one is effectively coordinating the entire operation.”54 To remedy this situation, the General Motors group recommended that the Spare Parts Board be abolished and that a “Spare Parts Service” be established in the Ordnance Department on the same level as the Industrial Service and Field Service. This recommendation was in accord with the spare parts organizations that prevailed in industry. The proposed service was to formulate spare parts policies and, when they were approved by the Chief of Ordnance, to be responsible for their execution. Acting on this recommendation, General Campbell on 26 June ordered the formation of a Parts Control Division as one of the six main units of the Ordnance Department.55 General Case, formerly commanding general of Aberdeen Proving Ground, was brought in to

be chief of the new division. Some of his staff came from the spare parts sections that were to be taken over by the Parts Control Division, while others came from among the General Motors experts who had made the survey.

Neither the order creating the new division nor the General Motors report went into any detail as to how the new division was to function. General Case and his staff were therefore at once faced with the task of determining their operating procedures. A difference of opinion soon emerged among the personnel of the new division as to whether it should take over all operations bearing on spare parts or should merely set up controls to. see that those responsible for such operations actually produced the desired results. Further, the General Motors people, who were experienced in peacetime supply problems of the automobile industry, did not see eye to eye with Ordnance officers who were familiar with the much different problems of wartime military supply.56 In the many conferences on these subjects held during the month of July, the wisdom of creating a Parts Control Division was seriously questioned.

General Case finally came to the conclusion toward the end of the month that the establishment of the division had been a mistake. Feeling that he had been put in the position of having responsibility without full authority, he recommended that the division be abolished, and that the spare parts problem be given to the Field Service,57 General Campbell reluctantly accepted General Case’s recommendation and abolished the Parts Control Division on 28 July—just four weeks after its creation. Responsibility for parts control was then turned over to the Field Service Division. The Spare Parts Board was re-established with essentially the same responsibilities it had had before the creation of the Parts Control Division, but its membership was now limited to two officers—the chiefs of the Industrial and the Field Service Divisions.58

With the elimination of Parts Control, the number of divisions was reduced to four—Industrial Service, Field Service, Technical, and Military Training. In terms of personnel and funds, every one of these divisions was many times larger than the entire Ordnance Department had been before the war. They had budgets running into the hundreds of millions of dollars and directed the activities of many thousands of officers, enlisted men, and civilian workers. Of their relationship to each other and to the Chief of Ordnance, General Campbell wrote:–

These divisions were largely autonomous. They were tied together as to the common policy and as to inter-division relations by me and my immediate personal staff. The heads of each of the divisions reported directly to me, as did also the heads of the Personnel, Fiscal, and Legal Branches. I tried to give each of them full authority, and I also tried to be completely frank with them at all times so that they, acting in a given situation, could have the maximum background on which to base an action. I tried to impress upon them that the more decisions they gave, within general broad policy limitations, the more value to me they were. They were at all times to keep me advised of matters which their common sense indicated I should know; equally, their common sense was exercised to

keep unimportant things away from me. … My job as I saw it was to be the Chief of Ordnance and to be as free as time would permit, to think and to spend time in the selection of men. In practically every case I was able to fill the principal positions with men who could do the job far better than I could.59

The “Front Office Team”

In the new administration, General Campbell’s right-hand man was Colonel Raaen, his executive officer, but there were also several assistants who handled special assignments. Lt. Col. Paul M. Seleen, who had served with General Wesson as assistant for matters pertaining to Field Service and research and development, continued in this position on General Campbell’s staff, with the important additional duty of heading the War Aid Branch. Lt. Col. Everett P. Russell, a consulting engineer in civilian life, handled matters concerning the Industrial Service, and Col. Herbert R. White, a former General Motors executive, served as a “trouble shooter” on industrial production matters. Lt. Col. Leo A. Codd, the executive vice president of the Army Ordnance Association and editor of the magazine Army Ordnance, handled the public relations activities of the Department. These four officers, with Colonel Raaen and Lt. Col. Thomas Moore, aide to General Campbell, made up the “front office team” during nearly all of General Campbell’s term.60

Staff Branches

In addition to the changes on the operating division level, several were made during June among the staff branches of the former General Office. A Control Branch, an Explosives Safety Branch, and a War Aid Branch were established, and the Fiscal and Legal Division was split into the Fiscal Branch and the Legal Branch. At the same time an Ordnance Department Board was created to study Field Service operations. Most of these changes were results of developments within the Department that had been gradually unfolding during the preceding months, but the establishment of the Control Branch and the War Aid Branch were specifically directed by ASF headquarters.

The Control Branch was a new and unfamiliar piece of administrative machinery that was virtually forced upon Ordnance by ASF, and was not welcomed by officers in the Department,61 With the formation of ASF in March, a Control Division had been set up as a part of General Somervell’s staff, and the proposal was advanced that corresponding control units be formed in all of the supply services. Because of the reluctance to accept this innovation, no final action was taken on the matter for over three months.

When the Ordnance Control Branch was finally established at the end of June, it was placed under the direction of Col. Clarence E. Davies, former executive officer to General Lewis in the Industrial

Service.62 Steps were then taken to recruit a competent staff of officers and civilians, but progress was slow.63 The new branch was charged with broad responsibilities for obtaining information regarding the efficiency of operation of all elements of the Department, recommending changes in organization, procedures, and policies, and managing statistical and reporting activities. Actually, the Control Branch seldom went beyond more or less routine functions and never achieved the position of influence that ASF wished it to have. In terms of initiative, rate of progress, and ability to get its recommendations put into effect, the Ordnance Control Branch was repeatedly given a low rating, as compared with similar branches in other services, by the ASF Control Division.64

Much of the difficulty ASF experienced with the Control Branch sprang from a misunderstanding within Ordnance of the functions of such a branch. The name itself was not accurately descriptive. General Somervell did not intend that the ASF Control Division should actually exercise control over day-to-day operations, but only that it should be an investigative and fact-finding agency to study organizational matters and help him keep informed about rates of progress, or lack of progress, in the many diverse activities of his command.65 General Wesson, taking a literal interpretation of the name, had assumed that the Control Division was to be an agency that would actually exercise control over operating personnel. When first approached by ASF representatives on this matter in 1942, he is reported to have declared that Ordnance did not need any such unit because he himself exercised full control of the Department. Much of the friction that subsequently developed between ASF and Ordnance stemmed from this brusque refusal by General Wesson to consider the need for an Ordnance Control Branch. General Campbell, though less hostile toward the proposal, never had much enthusiasm for it except in terms of making organizational charts and preparing statistical studies.66

In September 1942, following a survey of the existing administrative machinery for handling lend-lease transactions, ASF directed that a war aid branch or division be established within each of the supply services.67 A Defense Aid Section, headed by Colonel Seleen, was already in existence in Ordnance, as part of the Executive Branch. To comply with the ASF directive, this section was simply renamed the War Aid Branch and given status equal to that of the other staff branches. The War Aid Branch (later redesignated International Aid Division) always remained a staff unit and never grew to large proportions because the basic policy of the Ordnance Department was to handle war aid transactions through the existing organization—procurement through the Industrial

Service and distribution and shipping through the Field Service.68

Before the summer of 1942 the legal functions of the Department had been performed in three separate sections created to serve special needs. General responsibility for advising the Chief of Ordnance on legal matters had traditionally been assigned to the Fiscal Division. Legal problems relating to patent applications had been handled separately by a section of the Technical Staff. A third legal section, formed by General Campbell in 1940 when he was assistant chief of the Industrial Service for facilities, had handled the work connected with the construction and operation of scores of government-owned, contractor-operated plants.69 With the armament program in full swing by the summer of 1942, the volume and complexity of the legal work relating to contracts, patents, taxes, price ceilings, and renegotiation of contracts mounted steadily. General Campbell therefore named Lt, Col. Irving A. Duffy, former assistant chief of the Fiscal and Legal Division, chief of a separate Legal Branch and gave him full authority to handle all the legal work of the Department.

District Offices

Another phase of the June 1942 reorganization was the change in the administration of the district offices. The volume of business handled in the districts rose to tremendous proportions during the spring of 1942, and it became apparent that the civilian chiefs, most of whom were prominent industrialists serving on a volunteer basis, could not devote their full time and energy to district affairs. General Campbell therefore assigned experienced Ordnance officers to be chiefs of the districts and the former civilian heads, now relieved of the day-to-day operating responsibilities, became top-level policy advisers. Of the appointments to the larger districts, General Lewis was assigned to Boston, General Minton to Pittsburgh, Brig. Gen. Walter P. Boatwright to New York, Colonel Quinton to Detroit, Col. Guy H. Drewry to Springfield, Col. David N. Hauseman to Philadelphia, and Col. Merle H. Davis to St. Louis.70 Later, as demands for Regular officers had to be met for service in the field and elsewhere, many of these men were replaced by Reserve officers or by leading local industrialists.

At the same time, a uniform organization for all districts was prescribed, a plan that had been under study for several months by a board of officers headed by Col. Fred A. McMahon. Before this time the districts had been developing rather diverse structures. In 1935, when most district offices were staffed by only a volunteer civilian chief, one Ordnance officer, and a secretary, Ordnance had published a model for district wartime organization, but it had not been made mandatory as its authors felt that each district chief should have broad discretionary powers in developing his organization. The prescribed pattern of June 1942 paralleled that of the Industrial Division and thus facilitated communication between the districts and the Washington headquarters.71

After he had been in office for eight months, General Campbell wrote to ASF

describing the progress the Department had made since the start of the defense period, and the nature of the organizational problems that had been faced.72 He pointed out that by December 1942 the dollar value of Ordnance production had risen to something over one billion dollars a month, and contrasted that figure with the meagre appropriations available to the Department during the 1920s and 1930s. He conceded that there had been mistakes, false starts, inefficiency, and some duplication of effort. No organization could have expanded as fast as Ordnance did in the hectic atmosphere of wartime Washington with anything like normal peacetime efficiency. But, wrote Campbell, the faults were not all within Ordnance—the top-heavy administrative structure of the War Department itself was a serious handicap to the operating agencies. He referred to the “multiplicity of layers above the Services” and cited, as one example, the large number of boards, offices, and commissions in the War Department that dealt with the single problem of personnel. “The result of this,” he declared, “is confusion, uncertainty, and delay in putting our own organization on the efficient basis that the importance of our work demands. We welcome the opportunity to demonstrate how we can do a better job with less people. We have much yet to do. Much is being done. Our work will be materially aided if the multiplicity of reviewing and inspecting agencies can be reduced.73

Decentralization of the Ordnance Department

Throughout World War II the Ordnance Department followed its traditional policy of decentralization to reduce the volume of administrative work that had to flow through the office of the Chief of Ordnance. Long before Pearl Harbor General Wesson had delegated a large measure of responsibility to existing Ordnance field agencies, and had transferred various headquarters sections from Washington to other parts of the country. When General Campbell became Chief of Ordnance in June he entered enthusiastically into the task of further decentralizing the Department and soon made Ordnance the leader among the supply services in delegating responsibility to field headquarters and in moving units out of Washington.74 In explaining his policy of decentralization to his staff, General Campbell frequently quoted the old adage, “If you want to eat an elephant, first cut him up into small pieces.” It was his firm conviction that the multibillion-dollar Ordnance program was far too big and too complicated to be successfully administered from a single headquarters in Washington and that it had to be “cut up into small pieces.”75

Field Director of Ammunition Plants

In applying this principle during the summer of 1942, General Campbell established the office of Field Director of Ammunition Plants (FDAP) in St. Louis to administer a group of about 60 government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) plants producing artillery ammunition under cost-plus-fixed-fee contracts.

St. Louis was chosen as the location for the FDAP office because it had excellent railroad and airplane connections with the ammunition plants and was “the natural hub of this three-billion-dollar wheel.”76 Office space was leased in the basement of the Scottish Rite Cathedral on Lindell Boulevard, a convenient location next door to the office of the St. Louis Ordnance District.

To staff the new headquarters twenty-five officers and thirty civilians, who had served as contract negotiators and administrators in the Ammunition Division of the Industrial Service, were transferred to St. Louis. Col. Theodore C. Gerber, an Ordnance officer with extensive experience in commanding GOCO plants, was appointed field director and was made responsible to the chief of the Ammunition Branch of the Industrial Division.77 The task of the FDAP was to analyze and coordinate the operations of the various ammunition plants under its jurisdiction, regulate the flow of raw material and parts to the plants, and help each contractor to benefit from the experience of the others. The type of cost-plus-fixed-fee contract under which the plants were operating was comparatively new and required close FDAP supervision to get all the contractors to adopt standard procedures for reporting costs, preparing statistical data, and using manpower efficiently. As the functions of the FDAP were gradually extended to include supervision of ammunition loading plants, the staff increased in size until it numbered more than 500 officers, including officers assigned to plants as well as those in the field director’s office. In December 1943 Colonel Gerber was given the additional duty of serving as chief of the Safety and Security Branch, which had its headquarters in Chicago. This step brought about a closer coordination of the efforts of those who were responsible for production and those who were concerned with matters of safety and security.

The Industrial Division established four other suboffices during the latter half of 1942. The first of these was the Small Arms Ammunition Suboffice, formed by transferring the Ammunition unit of the Small Arms Branch to Philadelphia and assigning to it responsibility for administering the contracts at twelve GOCO plants manufacturing small arms ammunition.78 A second suboffice was established in Philadelphia at the same time by transferring to that city the Inspection Gage Section of the Production Service Branch to handle all matters pertaining to the procurement of inspection gages and the expansion of gage facilities.79 A third sub-office of the Industrial Division, established at Rock Island Arsenal late in August, was assigned engineering and inspection functions for all types of field carriages, and in December a suboffice for mobile artillery was also established at Rock Island,

The Tank-Automotive Center

On 17 July 1942, the day the FDAP was established in St. Louis, General Somervell issued an order transferring to the Ordnance Department within six weeks all the automotive activities of the Quartermaster Corps except operating units.80 This action was taken in order to centralize in the Ordnance Department control over the development, production, distribution, and maintenance of vehicles, which had many common elements—engines, transmissions, and axles—and was intended to eliminate duplication of effort by the two supply services in dealing with the automotive industry. To the Department’s traditional responsibility for combat vehicles such as tanks and armored cars, was now added the responsibility for trucks, passenger cars, ambulances, jeeps, and other types of transport vehicles.

In terms of organization, the order of 17 July meant that the civilian and military personnel of the Motor Transport Service (NITS), and all Quartermaster motor bases, motor supply depots, and schools for automobile mechanics were to be transferred to the Ordnance Department. The administration of more than 4,000 contracts with a total value of nearly three billion dollars was taken over by Ordnance. It was by far the largest single addition to the Department made during the war and, because of its magnitude, was a gradual process of absorption.81

To manage this enormous automotive production and distribution program, the Department made a move that one observer called “the boldest stroke of decentralization the country has yet seen in this war.”82 The Tank-Automotive Center in Detroit was established in the heart of the automobile manufacturing industry, and to it was delegated a large degree of authority and responsibility. The new headquarters was formed during September and October by moving the Motor Transport Service and the Tank and Combat Vehicle Division from their Washington offices to the Union Guardian Building in Detroit, along with other branches of the Ordnance Department concerned with tank and automotive matters.

The main reasons for this action were General Campbell’s concern lest there be too great a concentration of Ordnance functions in Washington and his desire to establish the closest possible relations with the automobile industry in the Detroit area. Office space in Washington was at a premium in 1942, as was housing for both military and civilian personnel. Agencies of the federal government had been urged to decentralize their operations wherever possible. General Somervell was keenly interested in decentralization within the technical services, and the Control Division of his headquarters had recommended transfer of the Tank and Combat Vehicle Division to Detroit or some other city. All of these factors had a bearing on the decision finally reached in August to establish the T-AC in Detroit.83

Brig. Gen. Donald Armstrong took the

Chart 6: Organization of the Tank-Automotive Center

first steps to establish the T-AC in August, and was joined a short time later by Brig. Gen. John K. Christmas.84 In September, Mr. A. R. Glancy accepted a reserve commission as brigadier general and became deputy chief of Ordnance in charge of the tank-automotive activities of the Department in Detroit.85 General Campbell selected these three officers for the Detroit headquarters because each had special qualifications for the job, which was partly industrial and partly military in nature. General Glancy, the chief of the T-AC, was an industrialist with experience in military procurement and production problems. General Armstrong, deputy chief of the center, was a Regular Army officer with experience in procurement, distribution, and supply. General Christmas, who had devoted most of his military career to tank design and engineering, became the chief engineer of the T-AC. But this arrangement proved to be unsound and was soon abandoned. As one officer commented, it provided “too many chiefs and not enough Indians.” The situation was further complicated by the fact that Generals Glancy and Armstrong were not suited by temperament and background to pull together in the same harness. Within a few months, General Armstrong was named chief of the Ordnance Training Center at Aberdeen Proving Ground and General Glancy was left in full command of the center, with General Christmas as his deputy.86

Under these circumstances, the T-AC was naturally beset with many administrative difficulties during the first few months of its existence. It was impossible to establish such a large headquarters, and at the same time integrate the Motor Transport Service with Ordnance, without going through a shakedown period. During these trying months, many criticisms of the organization and functioning of the T-AC came to General Campbell from ASF, particularly of the organizational structure and lines of authority. But by the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor—just three months after the creation of the T-AC—General Glancy was able to report: “Now that all our organization charts, manning charts, flow charts, and job sheets have been written, I doubt if there is another organization in the whole Army whose lines of authority and scope of activities are as clearly defined,”87

One feature of the TAC organization adopted by General Glancy was the staff of five directors who stood between the chiefs of the operating branches and the commanding general. Each director was assigned to a product specialty—tanks and combat vehicles, transport vehicles, parts and supplies, tools and equipment, and rubber products. Each was an expert in his own field, and each was given broad responsibility for supervising and coordinating the work of the appropriate sections of the operating branches. The Director of Transport Vehicles, for example, who was a Motor Transport Service officer of long experience, worked closely with the transport vehicle sections of the Development, Engineering, Manufacturing, Supply, and Maintenance

Branches, while the Director of Tanks and Combat Vehicles supervised the combat vehicle sections of the branches.88 Appointment of these directors was an attempt on General Glancy’s part to create an executive committee for the T-AC. He felt that any organization as large as the Detroit center, or as large as the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington, needed the kind of executive committee found in industry—a small group of mature, highly qualified men who would spend their full time watching the whole operation, advising on major policy decisions, and handling major problems as they came up. But, finding this concept foreign to traditional Army organization, he never put it into full operation in Detroit.89

By the end of June 1943 ill health forced General Glancy to relinquish his duties at the center, and General Boatwright, chief of the New York Ordnance District, was appointed to succeed him.90 Within the following three months the new commanding general made a number of organizational changes, most important of which were the elimination of the directors and the establishment of an Operations Planning Branch headed by Col. Graeme K. Howard, a former General Motors executive. The new branch was given responsibility for coordinating projects common to two or more of the operating branches and thus assumed a large part of the job formerly handled by the directors.91

General Boatwright’s tenure as chief of the center was marked by several important steps taken to strengthen the supply organization, for the year 1943 brought to the T-AC, as to the Ordnance Department and all the other supply services, the need for closer attention to stock control, storage, and distribution functions. Brig. Gen. Stewart E. Reimel was appointed assistant-chief for supply and maintenance and was given a position in the organization on a par with that of General Christmas, who remained as assistant chief for development, engineering, and manufacturing. A short time later two new branches—Storage and Redistribution—were added to cope with the task of maintaining a constant flow of vehicles and spare parts to and from distant theaters of operations.92

The T-AC was not only the largest of all the decentralized offices established by the Ordnance Department during the war but, unlike the other suboffices which were agencies of particular divisions or branches of the Department, the T-AC represented all of the major divisions. It was, as its later title of Office, Chief of Ordnance-Detroit (OCO-D) indicated, a replica of the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington.93 The size and importance of the organization are indicated by the fact that during the course of the war it spent nearly 50 percent of all the funds allocated to the entire Ordnance Department. It directed the production of more than three million vehicles, ranging from bicycles to

70-ton tanks. Its personnel strength grew from 40 officers and 593 civilians in September 1942 to 500 officers and 3,800 civilians by February 1943.94 These figures support the conclusion reached by Colonel Raaen, Ordnance executive officer, that “the establishment of the Tank-Automotive Center … was the greatest step taken toward decentralization since the Ordnance district offices were established during the last war.”95

In the opinion of officers who served in the OCO-D, one of the major lessons learned from the experience was the need for clear-cut delegation of authority by the headquarters in Washington. Many of the difficulties experienced by the Detroit office during the war were due to the fact that not all of the division chiefs in Washington delegated full authority to their representatives in the OCO-D. It was General Campbell’s intention that the Washington office should exercise only staff functions and that the Detroit office should be the operating level. But there were many different interpretations as to what was a staff and what was an operating function. “On the one hand,” a Control Division report stated in 1944, “offices in Detroit believe that Washington exceeds the bounds of staff supervision and indulges in operations to the point of interference, while on the other hand, some officers in Washington feel that staff supervision properly may be carried to any point that the staff officers feel is necessary in order to achieve effective results and that, where Washington has gone into operating details, it has been justified by failure on the part of Detroit to take prompt and effective measures, or by other sufficient reasons.”96

These difficulties were greater in supply and maintenance than in production and procurement. In general, there was more complete delegation of authority to the OCO-D by the Industrial Division in Washington than by the Field Service Division. Commenting after the war on this phase of Ordnance operations, General Boatwright stated that securing full cooperation between the various subordinate groups in Washington and Detroit was one of his most difficult problems in 1943, OCO-D was organized on a product basis well understood by the Industrial Service but not so well understood by the Field Service, which had an essentially functional organization.97

Other elements were also in the picture. The tank-automotive section of the Industrial Division, which became the manufacturing-engineering branch of the OCO-D, had been physically transferred to Detroit in the fall of 1942 as a going concern under General Christmas and had been given relatively free rein at the outset, but General Reimel only gradually built up the maintenance-supply organization after the Detroit headquarters was established. As a result, the Industrial Division in Washington tended to give greater freedom of action to the manufacturing branch in Detroit than the Field Service Division gave to the maintenance and supply branches. In addition, there was within the maintenance and supply branches a large proportion of former Quartermaster officers who had just recently been transferred to the Ordnance Department and who did not have close

personal ties, based on long years of association, with their opposite numbers in Washington. Finally, there was the feeling among some officers, both in Washington and Detroit, that the supply-maintenance functions should never have been assigned to the OCO-D at all but should have been kept within the Field Service Division or delegated to some other subordinate command. When asked, after the war, to evaluate the Detroit experiment in decentralization on the basis of his experience, General Christmas summed up the matter in these words:

Decentralization by General Campbell in 1942 of substantially half of his office (and substantially half of the money value of his program) to Detroit, was a bold and far-seeing move. I consider that it was highly successful and contributed greatly to the outstanding success of the Ordnance Department.

But it is no secret that the operation of the OCO-D, employing some 500 officers and nearly 5,000 civilians, was not accomplished without some wear and tear on the people in charge (both in Detroit and Washington) nor without some inefficiency and error. These I lay to two factors: (a) The functional organization of the higher echelon of the Ordnance Department, which cut across the essentially commodity organization of the OCO-D, which had been given complete responsibility for all automotive vehicles under the Chief of Ordnance and his staff. (b) The fact that it takes a long time to get such a new idea across to most people. Hence, there were people in the Office, Chief of Ordnance-Washington, who either misunderstood the object of decentralization, were out of sympathy with it, or in some few cases, as so often happens, had personal reasons for opposing it.98

Field Service Zones

At the same time that the FDAP was being established in St. Louis, and the T-AC in Detroit, seven zone offices were established by the Field Service Division to decentralize the administration of its depots.99 This step was taken largely be- cause the Ordnance Department, following the transfer of transport vehicles from the Quartermaster Corps, had assumed responsibility for approximately 55,000,000 additional square feet of storage space, including eight motor bases, four motor supply depots, eleven motor supply sections, one motor reception park, and two training centers. This had brought to more than sixty the total number of depots and other field establishments under the jurisdiction of the Field Service, and had added to the mounting volume of administrative work in the Washington headquarters of the Field Service Division. To provide for decentralized administration and management of these widely scattered establishments, seven zones were marked out on the map, with headquarters at Albany, New York, Baltimore, Maryland, Indianapolis, Indiana, Augusta, Georgia (moved within a few weeks to Atlanta, Georgia), Shreveport, Louisiana, Pueblo, Colorado, and Salt Lake City, Utah.100 Each zone office had from seven to twelve depots under its supervision, and served as an intermediate headquarters between these installations and the Office, Chief of Ordnance.

After six months the zones were abolished and the depots again came directly under the Field Service Division in

Washington. The zone offices were closed early in April 1943 because experience had shown that, instead of eliminating unnecessary administrative work, the zones had simply become “yet another channel through which reports and directives funneled.101 General Campbell and the chief of the Field Service Division, General Hatcher, were in agreement that the zone offices had become bottlenecks that slowed up operations and that their discontinuance would result in a great saving of manpower.102

Developments, 1943–45

The organization of the Department remained relatively stable during the 194345 period, (See charts dated 6 July 1944 and 14 August 1945.) Changes occurred in the names of various units, and occasionally functions were reassigned, but there was no modification of the broad outlines of the organizational structure. In June 1944 the word “service” came back into use to replace “division” as the designation of the major units of the Department, and at the same time all the staff branches were renamed divisions.103 The four main operating units—Industrial, Field Service, Technical, and Training—continued as the major elements of the Department, and, except in name, the eleven staff branches existing at the end of 1942 continued throughout the war. Early in 1943 the Department reached the peak of its wartime expansion, and after that time more and more attention was given to tightening up the existing organization, economizing in the use of manpower and essential raw materials, and carefully scrutinizing all production schedules and stock inventories.

Of all the major divisions of the Department, the Field Service experienced the greatest number of organizational changes during the 1943–45 period. This was chiefly because of a significant shift of emphasis in the operation of the Department that took place during the latter half of 1942. Throughout the preceding two years, first priority had necessarily been given to production, and the Industrial Service had occupied the center of the stage. At the end of 1942 the Field Service came to the front as munitions of all kinds came off the assembly lines in mountainous quantities and created serious problems in storage, distribution, maintenance, and stock control. As war production moved into high gear, and as large overseas movements of men and matériel got under way, the scale and complexity of supply operations reached unprecedented proportions and placed a severe strain on the Field Service Division.104 The recommendations of a special advisory staff, combined with pressure from ASF headquarters to make the division correspond more closely to the pattern of ASF organization, accounted for the revisions made in the Field Service organization at this time.

In January 1943 General Hatcher replaced General Kutz as chief of the division. A short time later a Military Plans and Organizations Branch was formed to obtain information from higher headquarters on projected troop movements overseas and use it as a basis for scheduling

Chart 7: Organization of the Ordnance Department: 6 July 1944

operations within the Division.105 A Field Service Control Branch was created in April to comply with orders from ASF headquarters that the Ordnance Department set up control branches in each of its main operating divisions.106

The most important change in the organization of the Field Service Division during 1943 was the creation of the Storage Branch and Stock Control Branch in August. This move came as a result of direct orders from ASF headquarters and was reluctantly accepted by the Ordnance Department. In organizing his staff at ASF headquarters, Maj. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, assistant chief of staff for operations, had established two separate divisions, one to deal with storage and the other with stock control. In April 1943 he directed the Ordnance Department to adopt the same type of functional organization in its Field Service Division.107 Neither General Campbell nor General Hatcher favored taking such a step. Both believed that the traditional Ordnance practice of assigning supply responsibility on a product basis should be continued, with the Ammunition Supply Branch handling all phases of ammunition supply, including storage and stock control, and the General Supply Branch handling all other types of Ordnance supplies.108 In the middle of May General Hatcher created a Supply Branch, made up of a Storage Section and a Stock Control Section. The Supply Branch, headed by Brig. Gen. R. S. Chavin, was a compromise between the ASF and Ordnance points of view, and did not last long. In August General Hatcher was forced to abolish the Supply Branch and to raise its two sections to the level of branches, on the same organizational plane as the existing Executive, Control, Maintenance, and Military Plans and Organizations Branches.109

During 1944 ASF ordered another change in the Field Service organization. To comply with the provisions of ASF Circular 67, General Hatcher appointed Colonel McMahon to serve as executive assistant for matériel control, Colonel McMahon was charged with responsibility for coordinating the activities of the Field Service Division, the Industrial Division, and the War Plans and Requirements Branch of the General Office on all matters relating to stock levels and distribution of supplies, and to maintain liaison for the Ordnance Department with ASF headquarters,110 After V-E Day Colonel McMahon’s title was changed to executive assistant for surplus military property, as increasing attention was given to the disposal of surplus matériel, particularly trucks and automotive parts for which there was a big demand in the civilian economy. A year later, when its functions were relatively routine, Colonel McMahon’s office was transferred to the Stock Control Division where it became the Surplus Property Branch.

The Military Training Service gained new responsibilities in 1944 when both the Military Plans and Organizations Branch of the Field Service and the Ordnance