Chapter 4: Back to the Pacific

I: The Third Division Emerges

ON its return to New Zealand the Fiji force was given the mobile role of army reserve, ready to operate in any part of the Dominion as required by the tactical situation but with particular attention to the Bay of Plenty, Auckland, and North Auckland districts and their vulnerable beaches. Headquarters closed in Fiji on 8 August, and the temporary headquarters which had been established by Potter in Quay Street, Auckland, to tide over the transition period, moved to Orford's House, Manurewa, which had been vacated by an American command. The two brigade headquarters were established at Papakura Camp, the 8th afterwards moving to Opaheke, with their battalions and services scattered widely over the surrounding countryside. The 29th Battalion was at Papakura, moving later to Hunua Falls, the 30th went to Karaka North, the 34th to Hilldene (Manurewa), the 35th to Paerata, the 36th took over buildings on the Avondale Racecourse, and the 37th went to Pukekohe. Some of these camps, temporarily erected to house American units while they trained for the Pacific campaign, were as bleak as the weather and ill-equipped, but all ranks went on leave, most of them suffering from colds and influenza induced by the sudden change from tropical heat to bitter spring wind and rain, against which battle dress and heavy woollens by day and five blankets and a greatcoat at night gave inadequate protection.

Although units were much below strength, commanders committed to paper their tactical plans for immediate movement and action, but it was generally assumed that the force would be built up to a full-strength division for service in the Pacific, in accordance with conversations between Admiral King and Mr. Nash in Washington earlier in the year in which it was stated that New Zealand troops, relieved from Fiji, could be trained for amphibious operations with United States forces if the essential equipment was provided. Such an assumption was also confirmation of General Puttick's conclusions, presented to the Minister of Defence

on 3 August, that ‘the best course to pursue in furthering the security of New Zealand is to participate to the fullest in offensive operations against the Japanese and at the same time leave nothing undone which may serve to strengthen the forces for home defence’; but reorganisation for any immediate action to implement this conclusion was slow and involved, and further provoked by indecision regarding the use of the force.

Major-General H. E. Barrowclough, DSO, MC, was appointed to command 3 Division on 12 August and arrived that day to begin the exacting and prolonged task of reorganisation. He had commanded 6 Brigade of 2 Division from its formation in May 1940, and had taken it through the ill-fated campaign in Greece and later through bitter fighting at Sidi Rezegh in North Africa. When the Japanese drive in the Pacific threatened to reach striking distance of New Zealand, the need for war-experienced senior officers became urgent, and he was recalled on the assumption that he would take command of the forces then in Fiji. However, before he reached the Dominion, the Pacific situation had become critical and Mead had already been appointed. Barrowclough was therefore given command of 1 Division, with headquarters at Whangarei, where he remained until he took over 3 Division. His immediate task was beset by difficulties and recurring problems. The precise role of the division in the Pacific and its size were as ill-defined as its title, and its history, in the early months of reorganisation, was shrouded in ambiguity. The title ‘3 Division’ had been in use since 14 May 1942 after the appearance of Mead's operational order No. 3 in Fiji, and that date, for record purposes and convenience, was taken as the day on which the force achieved the status of a division, but throughout the whole course of its existence the force was never officially gazetted ‘3 Division’ but remained legally ‘Pacific Section, 2 NZEF’, the designation it was given on 25 February 1942 when the original title ‘8 Brigade Group’ was amended. The letters ‘IP’, indicating the theatre in which the division operated, were added on 10 November when Barrowclough's appointment from ’Commander 3 NZ Division’ was altered to ‘General Officer Commanding 2 NZEF in Pacific’.

In making its decision to employ a division in the Pacific theatre, the New Zealand Government considered at the time that such a risk in sending men out of the country was justified. Great quantities of war materials, including tanks and aircraft, had reached the country; her home defences were therefore stronger and better equipped than ever before, and the situation beyond her shores was more secure because of the increased strength of the United States navy and island garrisons as far north as New

Caledonia. Five days before Barrowclough's appointment, American forces landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Gavutu, and although the Allied planners in London and Washington could not possibly be aware of the fact, Japanese orders for an attack on Fiji, New Caledonia, and Samoa had been cancelled in July, following the failure to capture Port Moresby and crushing losses of ships and aircraft in the Coral Sea and Midway naval battles. Political motives also contributed to the despatch of New Zealand forces to the Pacific theatre. The original intention of the American a command in asking for a New Zealand force was to use it for the relief of 1 Marine Division engaged in the Southern Solomons, but as the struggle for Guadalcanal developed critically by continued Japanese attempts to break the Americans on the Matanikau River line, any relief by other than American forces was not welcomed until the island was permanently secured. This was one of several contributing factors affecting the prolonged reorganisation of the division.

Delays in reaching a decision regarding the size of the force and the role it was to play in the Pacific campaign apparently stemmed from confusion over the expressed views of King and Ghormley, and were aggravated by manpower problems which had then begun to affect the supply of Grade I men for the three services as well as men for production at home. Although King agreed in June that New Zealand forces should take part in amphibious operations when the time came for offensive action then being planned, Ghormley, who had moved his headquarters from Auckland to Nouméa, apparently had expressed other views. During discussions with Puttick at the end of July, he suggested that New Zealand might provide forces to follow up United States amphibious troops and hold captured areas, in order to release specially trained and equipped American forces for further operations, the size of the New Zealand force to depend on the scope and locality in which it would be engaged.

Four alternative forces were proposed by Ghormley to meet any emergency—Force A, built round one infantry brigade with attached anti-aircraft and coast defence artillery; Force B, the same with the addition of two heavy coast defence batteries; Force C, built round two infantry brigades; and Force D, increased to three infantry brigades, each with additional coast defence and anti-aircraft artillery. Any of these forces, the size of which was to be determined by the Government, was to be ready for embarkation at any time after 25 August, and the proposal was obviously based on the American belief that the battle for Guadalcanal would end sooner than it did, as all future negotiations hinged on its success.

Puttick communicated Ghormley's proposals to War Cabinet on 31 July and recommended the adoption of Force Das a target for reorganisation, using 3 Division as a basis and adding the necessary units and services from existing New Zealand formations, the bulk of them to come from Army Reserve Brigade. At the same time he recommended the reduction of the age limit for service overseas from 21 to 20 years.

Although the original intention, as interpreted by Ghormley, seems to have been the employment of the division in a garrison role, other ideas were seemingly held by the planners in Washington, for on 8 July Commodore Parry, while undertaking a mission there on his return to England, had cabled the result of conversations he had with the Navy staff which indicated that, in addition to a request for garrison troops, America would also require others for amphibious operations. Approval of an offensive role was confirmed by War Cabinet's minute of 11 August appointing Barrowclough ‘to take charge of the division that is to be formed and trained for offensive operations’, but this contained no formal decisions regarding the size of the force. The gravity of the situation in the Solomons at this time interrupted Fraser's mission to the United States, to which he had been invited by Roosevelt. His party included the Right Hon. J. G. Coates, Mr. Carl Berendsen and Mr. A. D. McIntosh, of the Prime Minister's Department, Mr. B. C. Ashwin, of the Treasury Department, Brigadier K. L. Stewart, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, and Mr. Patrick Hurley, United States Minister in New Zealand. They reached Nouméa and conferred with Ghormley a few hours after he had been advised of the outcome of the first naval battle off Guadalcanal on 9 August and the crippling loss of four cruisers. Ghormley was extremely agitated by these losses, which so gravely reduced his limited strength in heavier ships. He was so apprehensive of the future in the Pacific that Fraser and his party temporarily delayed their journey to the United States and returned immediately to Wellington, where the Prime Minister called a secret session of Parliament.

On 10 August, the day before Barrowclough's appointment by Cabinet, Ghormley's headquarters had been informed that New Zealand was planning to provide a division of approximately 20,000 men, as requested, and that it would be available from 25 August, which would have been impossible as the last units of 3 Division did not return from Fiji until 14 August and the force was not sufficiently trained for such immediate despatch. However, any urgent need for it was discouraged by the fluctuating battle situation on Guadalcanal. Meanwhile, Army Headquarters

decided to proceed with the preparation of a force designated Kiwi A (a code name for the purposes of reorganisation), which was really Ghormley's Force A strengthened by artillery. It was to be built round units of 14 Brigade and to consist of:

Divisional headquarters on a reduced scale

One infantry brigade, with an anti-tank battery of 12 guns

One field regiment of sixteen 25-pounder guns

One heavy anti-aircraft regiment of sixteen 3.7-inch guns

One light anti-aircraft regiment of thirty-six 40-millimeter guns

One heavy battery of four 6-inch guns

Two companies of engineers

Signals, supply, and medical units and a small base organisation

This formation was given urgent priority, but the commander was also to proceed with the organisation of a force known as Kiwi C (based on Ghormley's Force C) consisting of 13,500 all ranks and made up of:

Divisional headquarters

Two infantry brigades, each with an anti-tank battery of twelve guns

One field regiment of twenty-four 25-pounder guns

One heavy anti-aircraft regiment of twenty-four 3.7-inch guns

One light anti-aircraft regiment of forty-eight 40-millimetre guns

One heavy regiment of four 6- inch or eight 155-millimetre guns

Three companies of engineers

Signals, supply, and medical units and a base organisation

Negotiations concerning the composition of these forces were in progress before Barrowclough's appointment and continued long afterwards. No New Zealand commander, faced with the responsibility of taking combat troops overseas, was ever so harassed by proposals, uncertainty, and indecision, all of which, despite his initiative and capacity for detailed planning, hindered him from reorganising his division and training to that desired state of efficiency required for an unusual campaign such as island warfare in the tropics. No details of the precise character of the operations were available to him, which was no fault of the New Zealand Army authorities, for even by 7 September the South Pacific commander had not received permission from the Dominion to use the Division. This was revealed when a signal from New Zealand requesting a supply of anti-malarial drugs brought a reply from Ghormley that he had not yet obtained the permission of the New Zealand Government to use its troops, nor did he intend to use them in a forward area while the situation there remained critical. Later, however, South Pacific Headquarters did indicate that the New Zealand force would not be required to carry out opposed landings, but that its role most probably would be to garrison small islands and take part in land attacks on large islands

or the mainland and that, in such operations, the possibility of heavy counter-attacks required full-scale supporting weapons and a high percentage of anti-aircraft and coast defence guns.

This question of artillery support was one of the most pressing problems which exercised the attention of the commander during the reorganisation period, and his views on its tactical significance were set out in a long letter to Army Headquarters. His idea of combat teams outlined in his letter was fully developed in training the division:

‘For a long time I have been teaching that success in modern war against a resolute and well-equipped enemy can be achieved only by a much closer co-ordination between infantry and artillery (and tanks if you can get them). I think, and I have long been teaching, that it is altogether wrong to consider the tactical handling of infantry as such in any unit larger than a platoon. I submit it is unsound to contemplate the employment of a company of infantry. One should command a mixed team of infantry, mortars, and guns. In battle a company command should never be a mere command of infantry. He should command a mixed team—a “combat team” as it is sometimes called... One of the mistakes of our British system is the tendency to over-centralise our artillery, tanks, and aircraft. Few battalion commanders and still fewer company commanders have any real idea of how to command a mixed force.’

In the original reorganisation plan only one field regiment was contemplated, but at the same time an anti-aircraft brigade, as part of the division, was to be formed and trained. Barrowclough's comments during exchanges of correspondence concerning the formation of Force A—which he considered unbalanced because anti-aircraft and coast defence guns required adequate ground protection—and Force C brought about changes, though Army did not agree the Force A was unbalanced.

‘From the outset’, he wrote, ‘even with Force C, I am limited to one field regiment of 25-pounder guns. The normal allocation of 25-pounders is on the scale of one field regiment to an infantry brigade, and I submit that until the precise task is known Force A should be mobilised and got ready in New Zealand with a full field regiment and Force C with two such regiments. Should the task, when it is known, call for less, field artillery guns can be left behind. The 25-pounde seems to be the one piece of equipment in which we outstandingly surpass our enemies, and I submit that neither Force A nor Force C can be considered adequately equipped if it has less than the usual scale of these guns.’

The commander also stressed the restricted mobility of such heavy pieces as 3.7-inch howitzers and 155-millimetre guns because, in possible engagements in areas removed from the site of static defence guns, they could not possibly take the place of 25-pounders, and they could be moved only with difficulty.

Because of the unusual composition of the force, the first of its kind New Zealand ever assembled, and its ultimate role, artillery remained a problem and eventually produced an organisation unique in the history of British arms. The division needed to be sufficiently strong to fight with or without the Americans (though it never did), and the necessity for static coast defence and anti-aircraft units, as well as support for infantry, required its artillery to be stronger and quite unlike the normal requirements of a divisional formation in the field. Two staffs were therefore evolved for its efficient operation—one for field and anti-tank units and another for coast defence and anti-aircraft. Each had its brigade major, staff captain and liaison officers, sharing a common intelligence officer, and this system worked satisfactorily in New Caledonia, where a regiment of 6-inch guns assisted with the defence of Nouméa Harbour and two anti-aircraft regiments defended several aerodromes. When the division moved north into the Solomons and the static units were disbanded and absorbed into other formations, the staff was proportionately reduced to the normal organisation.

The lengthy and complicated task of reorganisation no doubt provoked quite understandable impatience on the part of those most intimately concerned with it. Although in June orders had been issued that all available A grade men from ballots and garrison units were to be posted to divisions in order to have sufficient ready to meet the needs for overseas service, Army Headquarters, in calling for men for 3 Division, did not wish to weaken unduly the home defences by drawing off too many key personnel until the situation in the Solomons removed any threat of attack. There were delays, also, in hearing appeals of men balloted for overseas service and in medical boardings, and there was the provocative question of leave, made worse when many of the men taking the leave due to them after service in Fiji displayed no great haste in returning to their units.

Leave in New Zealand, approved by Army Headquarters, was arranged on a basis of seven days for every two months of service, with one-way travelling time and a free rail warrant, which meant that men from the southern districts stationed in the Auckland area spent almost a fortnight away from their units. Bereavement and confinement leave were also allowed up to seven and fourteen days respectively. This embarrassed the transport services (at that time hampered by coal strikes) as much as any training programme and produced a routine order from the 14 Brigade Commander in which he said: ‘Our primary duty is preparation for war and leave cannot be allowed to prevent the army from attaining a proper standard of training. Training is not only an individual concern;

it necessitates the presence of whole units and formations in the field together.’ During his inspection of both brigades, Barrowclough also emphasised that the war would not be won by staying in New Zealand and that sooner or later someone had to go overseas. In an attempt to reconcile to the best possible extent the conflict between a desire for leave, the need for training, and the difficulties of transport. Army Headquarters called a conference of all divisional and district commanders and, although War Cabinet approved its recommendations for certain modifications, leave was still generously granted.

Concentration on defence works by all ranks in Fiji had left little time for advanced training, and most of the units were unfamiliar with battle exercises on a large scale or the latest developments in jungle tactics, these last evolved from information reaching the training manuals from those who had been in contact with the Japanese. This was revealed when Barrowclough reported that ‘not one of the commanding officers was able to describe to me a single large-scale battalion exercise completely carried through’. For these reasons a six weeks’ programme of concentrated training was devised and on 1 September the South Pacific command informed that the force could not be ready for overseas operations before the middle of October. As the men returned from leave and reinforcements arrived to build up old and new units, brigades embarked on tactical exercises and battalions on manoeuvres, both by day and night, rain or shine.

All these were made as practical and interesting as possible and involved all branches of training so that, in the event of any sudden move, some reasonable state of preparedness would be attained. Engineers staged field days instructing the infantry in the art of bridging streams and in demolition; aircraft flew over the training areas trailing drogues as targets to accustom the men in anti-aircraft defence; lectures were given on malaria and other tropical diseases by former officials from the Solomons, and particular attention was paid to jungle warfare. Tactical exercises without troops concerned the senior officers, who were no longer required to find men daily for digging and wiring and excavating, as they had done in Fiji. A field regiment and anti-tank batteries were reorganised from the existing units from Fiji and took part in combined attack and defence schemes, but elements of coast and anti-aircraft artillery formations, these last beginning at the recruit stage, were concentrated in camps at Judgeford and Pahautanui in the Wellington area under Colonel V. A. Young, RA, who was responsible for their organisation and training until they were ready to be absorbed into the division under the new CRA,

Brigadier C. S. J. Duff, DSO.1 When these units finally emerged from the cocoon of reorganisation, they moved north via Rotorua, holding, calibration shoots on the way, and joined the division in the Waikato.

In order to avoid any confusion and unnecessary duplication in training, organisation and equipment, which arose because of the idea that attention could be given to Force C after Force A had left the country, Barrowclough on 1 September asked for a definite ruling from Army Headquarters, at the same time expressing the opinion that reorganisation would be effected more smoothly if the force was considered as a division less one brigade. Some idea of the difficulties being faced at this time, when no definite answer was possible, are indicated in a paragraph from Army's reply to the commander:

‘I do not intend to bore you with the difficulties with which Army Headquarters and districts have to contend to produce personnel for your division, but I would ask you to accept them as very real.... Unfortunately a good deal of patience and restraint will require to be exercised by us all in many matters connected with this force.’

Carelessness by districts in selecting men for reinforcements for the division aggravated many of the delays in strengthening units, and a base reception depot established in Papakura Camp was hard pressed to cope with the constant stream of arrivals and departures. The figures for three months are eloquent evidence of the work required at this depot in detail and record:

| Sep/Oct | Nov | |

| Marched in | 1763 | 998 |

| Marched out | 880 | 346 |

Among those marched out were the medically unfit or lower than Grade I, men with more than three dependent children, incorrigibles, men over or under age, all half-caste or full-blood Maoris, and from quarter- to half-caste Maoris if they so desired. A high percentage of those marched out as unfit were men sent forward as reinforcements.

Manpower governed to a great extent the assembly and training of all units and affected the fortunes of the division during its whole existence. By the end of 1942 New Zealand was already feeling the strain of supporting two active service divisions and in maintaining her commitments to the Air Force and the Navy, as well as her home defences and garrisons in Tonga, Fiji, and

numerous smaller islands, including scattered groups of coastwatchers. Production on the home front, so essential to the war effort principally in the supply of food, wool, coal, and munitions, was being maintained but showed little signs of increasing. (See Chapter 3, page 59.) Through all the complex detail of reorganisation, therefore, manpower loomed up like a restraining hand, but by the end of September formation was reasonably complete. One of Barrowclough's most immediate tasks on assuming command was the selection of commands and staff, which he did thoroughly by personally interviewing those who returned from Fiji. Many of the senior officers exceeded the age limit and several of the staff appointments were vacant or held only temporarily. Their places were taken by younger and more vigorous men, selected preferably from those with staff college training or others who had returned after service with 2 Division in the Middle East. Though still far from complete in detail, by early October the framework of the division was as follows:2

|

Divisional Headquarters | |

| GOC | Maj-Gen H. E. Barrowclough, DSO and bar, MC |

| GSO 1 | Lt-Col J. I. Brooke |

| GSO 2 | Maj S. S. H. Berkeley |

| GSO 3 (Operations) | Capt R. F. Wakefield |

| GSO 3 (Intelligence) | Capt J. Rutherford |

| AA and QMG | Col W. Murphy, MC |

| DAQMG | Maj P. L. Bennett, MC |

| DAAG | Maj S. F. Marshall |

| Chief Legal Officer | Maj D. A. Solomon |

|

Artillery | |

| Commander Royal Artillery | Col C. S. J. Duff, DSO |

| Brigade Major (field) | Maj N. W. M. Hawkins |

| Staff Captain (field) | Capt O. J. Cooke |

| Brigade Major (A/A and coast) | Maj C. D. B. Campling |

| Staff Captain (A/A and coast) | Capt J. A. Crawley |

|

33 Heavy Coast Regiment: | |

| Commander | Lt-Col B. Wicksteed |

| 150 Battery | Maj H. C. F. Peterson |

| 151 Battery | Maj J. G. Warrington |

| 152 Battery | Maj G. L. Falck |

|

17 Field Regiment: | |

| Commander | Lt-Col H. W. D. Blake |

| 12 Battery | Maj R. V. M. Wylde-Brown |

| 35 Battery | Maj A. G. Coulam |

| 37 Battery | Capt D. O. Watson |

|

28 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment: | |

| Commander | Lt-Col W. S. McKinnon |

| 202 Battery | Maj E. M. Luxford |

| 203 Battery | Maj H. G. St. V. Beechey |

| 204 Battery | Capt B. S. Cole |

|

29 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment: | |

| Commander | Lt-Col F. M. Yendell |

| 207 Battery | Capt H. L. G. Macindoe |

| 208 Battery | Capt B. L. Burns |

| 209 Battery | Capt G. H. Turner |

| 214 Battery | Capt G. F. T. Hall |

|

144 Independent Battery: | |

| Commander | Maj L. J. Fahey |

| 53 Anti-Tank Battery | Capt L. D. Lovelock |

| 54 Anti-Tank Battery | Capt R. M. Foreman |

|

Engineers | |

| Commander Royal Engineers | Lt-Col A. Murray |

| 20 Field Company | Maj W. G. McKay |

| 23 Field Company | Capt A. H. Johnston |

| 37 Field Park | Capt S. E. Anderson |

|

Singals | |

| Chief Signals Officer | Lt-Col D. McN. Burns |

| Artillery Signals | Capt G. W. Heatherwick |

| No. 1 Company | Capt K. H. Wilson |

| Headquarters Company | Capt R. M. South |

| J Section (8 Brigade) | Lt G. M. Parkhouse |

| K Section (14 Brigade) | Lt C. G. Murray |

|

Army Service Corps | |

| Commander | Lt-Col F. G. M. Jenkins, DCM |

| Senior Supply Officer | Maj A. Craig |

| 4 ASC Company | Capt R. Gapes |

| 16 ASC Company | Capt A. M. Lamont |

| 10 Reserve Mechanical Transport Company | Capt L. M. G. Grieves |

|

Medical | |

| ADMS | Col J. M. Twhigg, DSO |

| 7 Field Ambulance | Lt-Col S. Hunter |

| 22 Field Ambulance | Lt-Col W. F. Shirer |

| 4 General Hospital | Lt-Col A. A. Tennent |

|

Dental | |

| ADDS | Lt-Col O. E. L. Rout |

| Base Dental Hospital | Maj J. C. M. Simmers |

| 10 Mobile Dental Section | Maj A. I. McCowan |

|

Ordnance | |

| DADOS | Maj M. S. Myers |

| Senior Mechanical Engineer (Armament) | Maj J. W. Evers |

| Senior Mechanical Engineer (MT) | Maj G. C. Simmiss |

|

Infantry | |

| 8 Infantry Brigade: | |

| Commander | Brig R. A. Row |

| Brigade Major | Maj J. M. Reidy |

| Staff Captain | Capt I. H. MacArthur |

| 29 Battalion | Lt-Col A. J. Moore |

| 34 Battalion | Lt-Col R. J. Eyre |

| 36 Battalion | Lt-Col J. W. Barry |

| 14 Infantry Brigade: | |

| Commander | Brig L. Potter |

| Brigade Major | Maj C. W. H. Ronaldson |

| Staff Captain | Capt A. E. Muir |

| 30 Battallion | Lt-Col S. A. McNamara, DCM |

| 35 Battalion | Lt-Col C. F. Seaward |

| 37 Battalion | Lt-Col A. H. L. Sugden |

|

Base Units | |

| Officer in Charge of Administration and Base Commandant | Col W. W. Dove, MC |

| DAG 2 Echelon | Capt G. W. Foote |

| Staff Captain | Lt H. N. Johnson |

| Base Reception Depot | Capt A. R. Stowell |

| Pay | Capt W. P. McGowan |

| Records | Lt E. R. Newman |

| Postal | 2 Lt F. W. Purton |

Many of the base units were not formed or were in process of formation and were completed only after long delay. Changes of appointment were frequent through the formative months, and many of the above appointments were altered by the end of the year.

Because of the unsuitability of some of the camps, and with a view to more comprehensive training and the use of troops for large-scale tactical exercises, a change of area was proposed, first to Warkworth, but finally to the Waikato. The division, however, seemed fated to periods of disintegration. New Zealand was

asked to provide more garrisons for the Pacific, and this meant the withdrawal of units from 3 Division. On 7 October 36 Battalion, with supporting artillery—field, coast, and anti-aircraft—was detached for duty on pine-clad Norfolk Island to relieve Australian troops there, and later in the month the 34th was despatched to Queen Salote's island kingdom of Tonga to replace an American unit. Both battalions rejoined the division later in New Caledonia. They were replaced in 8 Brigade by 1 Scottish Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel K. B. McKenzie-Muirson, MC,3 and 1 Ruahine Battalion, under Lieutenant-Colonel C. N. Devery, DCM,4 from 4 Division, though these two units did not join the division until it sailed for New Caledonia.

On 16 October, as the division was settling itself into the Waikato district, its role was to some extent clarified by a request from Ghormley's headquarters for a force equal to Force C to move to New Caledonia to replace American units committed to the battle, which was still undecided on Guadalcanal. The following day a cable despatched to Nash in Washington indicated its size: ‘War Cabinet have agreed to Ghormley's request for a New Zealand force of approximately two brigades to proceed to New Caledonia as soon as transport can be arranged.’ This was Force C of 13,500 all ranks, but a larger force, built round Force D, of three brigades, with increased artillery and services, was still evidently contemplated for the Pacific, as the following sentence appeared in a message from Puttick to the commander of the South Pacific area on 13 October: ‘Owing to manpower difficulties I cannot give estimated time when Kiwi D will be ready.’ Approval for the remaining third brigade was given by War Cabinet on 28 November, but it was not to be formed until after the division was concentrated overseas. Inclusion of an armoured regiment of 60 tanks and 900 all ranks was also approved by Cabinet on 5 November, and preparations for its assembly from units of 2 Army Tank Battalion began at Waiouru, but the main body did not go north until the division was on Guadalcanal the following year.

Few men regretted leaving for the Waikato during the first two weeks in October. Strengthening sunshine and lengthening days did little to compensate for the discomfort of cold hutted and tented camps, through which the wind whistled miserably, so that the more articulate expressed in no uncertain terms their longing

for the tropical heat they had cursed so volubly only a few weeks previously. Isolated in a YMCA camp at Hunua Falls, where exercises had been held in country which would have tried even the ingenuity of a goat, 29 Battalion departed happily from an area inches deep in mud; for two months 35 Battalion at Paerata had been attending its sick in a four-man but without such rudimentary equipment as a sink, light, or running water, this last a growing problems in most of these temporary camps. The only compensating factor was their proximity to Papakura, Pukekohe, and Auckland, which gave ample opportunity for evening and weekend leave, and in granting this Barrowclough departed from the orthodox military practice and insisted that if a soldier returned to camp in time and in a fit state to perform his duties the following morning, there was no necessity to crime him for not returning at any specified time the previous evening.

Units marched in stages to their new areas, bivouacking by night as part of the training scheme. Morale was good, esprit de corps asserted itself, and few fell by the wayside; if they did they were soon revived by the hospitality which was showered upon them. Reconnaissance parties had previously allotted areas over a vast triangle enclosed by Hamilton, Te Aroha and Tirau, and including Morrinsville, Cambridge, and Matamata. On 6 October, when the move began, Divisional Headquarters was established in buildings of the Claudelands Racecourse; 8 Brigade went to Cambridge and 14 Brigade to Te Aroha Showgrounds, with their units distributed around them. Artillery Headquarters, its units not yet fully assembled, was established at Tirau with its regiments in Okoroire and Matamata; Engineer units were housed on the Te Rapa Racecourse, ASC at Morrinsville, and Signals at Claudelands. Base units were installed at Rugby Park in Hamilton, where new units were still being added to the order of battle.

The Waikato, in the full flood of spring, was lush, warm, and beautiful. In every town and village occupied by troops, residents responded so generously with entertainment, both private and public, that the period spent there remained as warmly in the memory as the thermal springs within easy reach of Te Aroha, Okoroire, and Matamata. As soon as the move was completed, preparations began for large-scale tactical manoeuvres in the Kaimai Ranges which the commander had in mind when he selected the Waikato as a training area. These manoeuvres, afterwards referred to facetiously as the ‘Battle of the Kaimais’, were the first in which the Division as a whole, or as whole as it was ever to be, was engaged, and one of the most valuable because of the lessons learned and not readily forgotten.

In selecting this tract of wooded country Barrowclough had in mind the situation then existing in New Guinea, where the Japanese, after their reverse in the Coral Sea, were attempting to invade Port Moresby overland by crossing the Owen Stanley Ranges from Lae and Salamaua. The locality was ideal as a testing and training ground in jungle warfare for both men and equipment—only the heat and the mosquitoes were missing. Dense, untracked bush clothes hills rising to 2000 feet, through which a trail had been blazed as an axis of advance for the two opposing groups. For the purpose of the manoeuvre, which lasted from 21 to 27 October, Tauranga became Buna and Matamata represented Port Moresby, with the high country dividing them as the Owen Stanley Ranges.

Row's 8 Brigade, made up of 29 Battalion, 23 Field Company Engineers, 4 Composite Company ASC, 7 Field Ambulance and two home defence units, 1 Auckland and a Home Guard battalion from the Tauranga area, represented a Japanese force advancing through Tauranga; potter's 14 Brigade consisting of 30, 35, and 37 Battalions, 20 Field Company Engineers, 16 Composite Company ASC, and 22 Field Ambulance moved into the ranges from Matamata to meet the enemy. Advanced Headquarters opened at Opal Springs, a bucolic spot near the foothills where trees enclosed a warm water pool, appointed umpires and watched results. The Japanese force was to advance through ‘Buna’, continue into the bush, construct a road and gain contact with the enemy; the defending force, after moving out of ‘Port Moresby’ was to take up a position astride the line of advance (the ‘Kokoda Trail’) and maintain itself there for a week. This exercise was made as realistic as possible, its object being to practise the protection of supply convoys, the movement of infantry patrols through bush, communications, the organisation of medical services and other problems of administration. Air co-operation and air support played an important part. Hostile aircraft, dropping flour bombs, were represented by Hudson bombers escorted by Kittyhawk fighters, with Hawker Hind reconnaissance planes playing for the defenders, all of them coming from aerodromes at Tauranga and Whenuapai during the hours of daylight to engage in mock dive-bombing raids and to reconnoitre the positions of the opposing forces. Propaganda leaflets dropped by the ‘enemy’ in the 14 Brigade area proved to be ‘cheap immoral publications’ in the estimation of the intelligence staff who examined them.

Heavy rain fell soon after the manoeuvres began and continued in torrents, adding considerably to the realism of jungle warfare but without its enervating heat. Conditions in the bush rapidly deteriorated and were such that patrols from the two forces which evaded

each other were so exhausted they made no show of resistance when captured but simply asked for food. The 1st Auckland (T) Battalion, less arduously trained than 3 Division, was withdrawn after the first day. No formed roads existed on either side in the immediate neighbourhood of engaged units, so that the task of creating them fell to the engineers, using bulldozers. When the weather halted all traffic except four-wheel-drive vehicles using chains, the roads were corduroyed for miles with trunks of tree ferns. Bren carriers and jeeps soon churned deep tracks through the emerald slopes leading up the bush line, when they replaced the ASC supply columns which were bogged down. In the bush itself, in the 14 Brigade area, a steep four-foot track was cut in steps up the hillside, and here, stripped to the waist and often knee-deep in mud, men of the ASC passed cases of supplies from hand to hand to ration the fatigued and sodden troops in the combat areas. The Kaimai adventure emphasised what was realised later, that much of the Solomons campaign was to be an engineer and supply problem. This test of organisation equally tried the physical efficiency of the individual and the reliability of unit equipment. Signals discovered that the existing wireless sets were useless in the rain-soaked bush, and relied on line communication; engineers, working from six o’clock in the morning until late into the night, soon realised that jungle warfare required a considerable increase in established equipment; the infantry, burdened with full pack and 24 hours rations, emphasised the necessity and value of slashers and waterproof capes; the ASC, using jeeps to transport supplies over the boggy routes, finally resorted to the use of 1000 sandbags for the final individual carrying parties.

At the conclusion of the manoeuvre its shortcomings were ruthlessly exposed at a conference of commanders, during which Barrowclough commented that many of the troops, who were not fully aware of its purpose, seemed to think ‘they were the Tararua Tramping Club making a road and packing in supplies’. Instead of improving occupied positions troops were too concerned with settling in and building shelters to turn the rain; making tracks took precedence over lanes of fire and fire plans; localities were revealed to aircraft by smoke from fires, and little attention had been paid to camouflage. Because of the dismal conditions, commanders were to concerned with the comfort of the men instead of with the ‘enemy’. But the lessons learned were invaluable. Shortages were revealed, and the necessity shown for traffic control and anti-aircraft protection measures in rear areas, as well as an increase in unit equipment or its replacement by better quality articles. Two factors emerged triumphantly—the jeep as a means

of transport under the most desperate conditions and the morale of the men, for sick parades had fallen far below normal during the exercise. Even the medical units found they could use jeeps for the transport of casualties when their ambulances were bogged down in the mud. Though the New Zealand soldier does not play at manoeuvres with any great degree of enthusiasm, requiring rather the presence of the enemy and the stimulus of actual fighting conditions, those troops taking part in the Kaimai exercise achieved a realism which drew praise from a party of American officers who visited the scene of operations and saw them at work.

The division's impending departure for New Caledonia was revealed at the conclusion of the Kaimai manoeuvres, after which leave was granted before the final packing and medical examinations began with their usual bustle. Meanwhile, information was reaching headquarters about the new territory. Brooke5 flew to Guadalcanal, returning with first-hand knowledge of conditions there during the height of the battle and some experience of the heavy bombardment of Henderson airfield by Japanese warships. Dove6 and Rutherford7 brought back a sheaf of information about New Caledonia, to which they had flown on 18 October to select temporary headquarters and reconnoitre the proposed divisional areas. They were followed by an advanced party of 150 all ranks, under Major W. A. Bryden,8 which sailed in the Crescent City and reached Nouméa on 2 November. Barrowclough and his principal staff officers arrived there by air five days later to await the assembly of the main body.

II: Move to New Caledonia

Through November, December, and January the division moved overseas, though not before its carefully planned departure schedules were upset by changes in shipping and escorts. The Maui, carrying 1960 all ranks, mostly artillery units urgently required by the American command, reached Nouméa on Armistice Day, the commemoration ceremony for which was attended by representative New Zealanders. The Brastigi, with 917 men made up from Divisional Signals, 20 Field Company Engineers and 16 ASC Company, disembarked at the small coastal port of Nepoui

on 30 November, and was the first ship to use it; the Weltevreden, with 25, and the President Monroe, carrying 1796, mostly artillery, 30 Battalion and Base units, reached Nouméa together on 6 December; the West Point, taking the main body numbering 7158, reached Nouméa on 31 December; the Mormacport, with 249 members of rear parties, berthed at Nepoui on 6 January, and the Talamanca, with 226 more rear details, reached Nouméa on the 11th. By the end of February another 1052 details, including the usual collection of absentees without leave, had reached New Caledonia.

The movement of these 13,383 soldiers, together with a vast amount of stores and equipment, was made without mishap or excitement and was a lesson in American transport methods by which every available inch of space on large transport vessels was occupied. On large ships such as the West Point only two meals a day were served, which those returning from Fiji in the President Coolidge had already experienced and found the intervals between meals rather tiresome. Bunks, only two feet six inches apart, were in tiers four high in holds accommodating between 600 and 700 men. Meals and recreation periods on deck were taken in rotation, but the voyage was too short to be anything other than an interlude, pleasant or unpleasant according to individual preference. The President Monroe provided an interesting comment on war for the historically minded. Named after the president whose dominant motive was the prevention of European interference in American affairs, the ship was now transporting New Zealand soldiers to a French possession to assist in a war against Japan which had its origin in the German invasion of Poland. Monroe's portrait still adorned the ship's lounge.

New Caledonia, where during nine months of garrison duty 3 Division fitted itself for the Solomons campaign and established its base for those operations, lies 1000 miles north of New Zealand and 700 miles east of Australia, with its southern tip just over the Tropic of Capricorn. This French colonial possession, 248 miles long, never more than 31 miles wide, and shaped like a huge bread roll, is the world's richest island as a source of minerals. In 1938, with the exchange rate at 200 francs to the £, New Caledonia exported 19½ million francs worth of nickel, 21½ millions worth of chrome, and 12 millions worth of coffee, most of the minerals going to Germany and Japan, the only countries which wanted them. Until 1894 France made use of the island as a penal settlement, 40,000 prisoners passing through the convict barracks on Ile Nou, the largest island in Nouméa Harbour, before such traffic ceased, after which various colonisation schemes were attempted with little

success. Despite infrequent hurricanes, New Caledonia enjoys a magnificent climate for nine months of the year, half the annual 40 inches of rain falling in January, February, and March. Like most Pacific islands it has its wet and dry sides, but in both there is an abundance of freshwater streams, fed from a central chain of mountains.

Life moved indolently in picturesque Nouméa, the principal town, port, and seat of Government, until war suddenly transformed it into the largest forward Allied base in the Pacific, where its magnificent land-locked harbour, the entrance to which is guarded by a coral reef and a lighthouse presented by Napoleon III, sheltered every type of warship and transport. As the division's convoys reached the harbour they found it massed with ships, ranging from destroyers and landing craft to imposing aircraft carriers and battleships, several of them being repaired after disastrous engagements in and around Guadalcanal. Little space was available at the inadequate wharves, so that troops disembarked in the stream and were ferried ashore. Transports waited for weeks before they could berth and unload stores and heavy equipment.

Worse congestion was evident ashore, where headquarters of the South Pacific Command was established with all the subsidiary naval, military, and air headquarters and their staffs required for the conduct of an involved and widely dispersed campaign. Every vacant hillside and open space in and around the town was covered with hutted and tented camps. Vast dumps of war materials dotted the landscape for miles; aeroplanes linking New Caledonia with the battle zone and the network of Pacific bases extending to New Zealand, Australia, Fiji and beyond, were never absent from the sky, and ceaseless streams of motor traffic moved in dusty procession to and from the camps and aerodromes far in the country. Relations between the American command and French administration were strained, mostly because of the peremptory demands of war, but from the influx of thousands of servicemen flushed with money the local tradesmen and shopkeepers reaped their traditional wartime harvest.

But the men of the division saw relatively little of Nouméa, except on brief visits. Temporary Base Headquarters was established in Rue d’Alma, in the middle of the town, with staging camps at Dumbea, some miles away, to which troops were moved in an antiquated train only slightly better than the Colonial Sugar Refining Company's modest system in Fiji, and at Nepoui Valley, 160 miles north and a few miles inland from the port of that name, where clouds of choking red dust coated the scrubby trees

in the neighbourhood and departing aircraft on the nearby aerodrome were followed by mountainous dust-storms of their own making. Troops for Nepoui disembarked in Nouméa Harbour and were staged up the coast in smaller craft to avoid the long haul by motor transport, which was never sufficient to meet the demand. These camps served their purpose as the division moved in and assembled, after which a transit camp was established by Base in Nouméa to handle all through traffic while the New Zealanders remained in New Caledonia.

Immediately on arrival the division occupied an area on the dry side of the island stretching for more than one hundred miles from Moindou, where its southern boundary joined 43 American Division's territory, to the far north and included the Plaine des Gaiacs aerodrome, other airfields in the north, and the port of Nepoui. It consisted of gently undulating country covered for the most part with niaouli trees and rank grasses, rolling down to the coast from the central mountain divide and watered by numerous streams and rivers, all of which were subject to swift flooding.

Only two main roads served the whole area. One, Route Colonial No. 1, coiled its way from north to south and was the main arterial route. Despite the lethargic efforts of a few workmen using barrows and shovels to fill in the holes with soil from nearby pits, this soon broke under a constant stream of cars, trucks, and jeeps, each leading its individual cloud of dust. Narrow bridges, none too secure, crossed the larger streams; concreted fords to prevent erosion served the smaller courses, and in the far north, at Tamala, all traffic crossed the river by ferry. The other road crossed the island from Bourail through the mountains to join an inferior route at Houailou serving the wet and more verdant east coast, where most of the rivers were crossed by old-fashioned ferries controlled by hand winches. All subsidiary roads were unmetalled and soon churned to mud after rain.

The whole of the public services and amenities of New Caledonia were little better than those existing in New Zealand in the pioneering days and were typical of a neglect born of isolation, but the dry rolling country was excellent for camp sites and manoeuvres. There were few distractions. Villages were few and far between along the main roads and all of them rather blistered by time, with large cattle runs, bounded by rivers, coast and mountain, sub-dividing the rest of this sparsely populated country and supporting their independent and thrifty owners. Mosquitoes, of the non-malarial variety, were a constant source of irritation, particularly in the marshy country near the coast and in river valleys, where they

were unspeakably bad, but there were areas comparatively free from these pestilential insects. The only ports of any size and all the aerodromes were in the western side of New Caledonia, and round them the principal defences were concentrated.

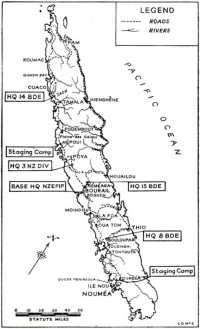

On arrival Barrowclough's force became a component of First Island Command, under Lieutenant-General Rush B. Lincoln, and, as such, a part of Vice-Admiral Halsey's South Pacific forces. Barrowclough assumed command of the northern sector of the island on 17 December, with the tactical role of defending the aerodromes, radar stations along the coast, and the beaches, several of which were vulnerable and widely separated. From temporary headquarters established on 23 November at Nemeara, on the Houailou road, he moved to a site among the niaoulis on terraces between the Moindah River and the main road and opened permanent headquarters there on 12 December. It was 160 miles north of Nouméa and twelve miles from Poya, the nearest village, but the mosquitoes were few and space was unlimited.

Mobility was the key to the division's role in New Caledonia, where amphibious landings were possible almost anywhere along the coast, but the central mountain range could be crossed only by large formations, guns, and vehicles along the Houailou-Bourail road, so that the east coast required little attention. The southern route to Nouméa was narrow and tortuous, allowing only one-way traffic where it ran through the hills from the division's southern boundary to Bouloupari. This problem could be solved by using Nepoui as a port and establishing dumps north of Moindou in the event of enemy action. Natives in the area round Hienghene, a village on the north-east coast, were suspected of Japanese sympathies, and unconfirmed reports of enemy submarines off reef passages there lent some support to this suspicion, but the majority of the natives were friendly and displayed the liveliest interest in the men of the Division.

Barrowclough decided that the most suitable plan to meet the situation was the provision of ample coastwatching detachments and the disposal of mobile formations capable of moving immediately to any threatened area, for which motor transport was now reasonably assured. The arrival of Goss with the skeleton headquarters of 15 Brigade gave the GOC three brigades of two battalions each, a most unsatisfactory organisation in the field, but the only one possible until New Zealand clarified the position regarding additional troops required to bring the division up to full strength and until his other two battalions returned from Norfolk and Tonga. As all the coast and most of the anti-aircraft artillery had, by mutual arrangement, been diverted for the

These were the final dispositions of 3 Division units in New Caledonia. The Division arrived in New Caledonia during November and December 1942 and January 1943 and departed the following August. The base organisation remained at Bourail.

defence of Nouméa Harbour, one of the most vital in the Pacific at that time, and the aerodromes north of Nouméa, which were equally vital in staging aircraft to Guadalcanal, the task of defending the sector was accomplished with only field, anti-tank, and two batteries of light anti-aircraft artillery. In disposing his division over vast stretches of country, the brigade group was developed and from it the battalion combat team, which is a self-contained force with an infantry battalion as a nucleus, supported by field, anti-tank, and anti-aircraft artillery, and including sections of engineers, field ambulance, and ASC.

The northern sector was allotted to 14 Brigade, which established its headquarters on flat, tree-clumped country beside the Taom River near Ouaco, with 35 Battalion in the immediate vicinity and 30 Battalion some miles north at Koumac. Potter's group also included 35 Field Battery, 53 Anti-Tank Battery, 209 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, 20 Field Company Engineers, 22 Field Ambulance with a field surgical unit and a 50-bed field hospital, 16 Composite Company ASC, 37 Light Aid Detachment, and one section of the Reserve Mechanical Transport Company. His task was the defence of two airfields at Koumac, radar stations at Pam and Gomen, at that time manned by American technicians, and the beaches. All French and native home defence forces, not of any great consequence, came under his command.

Eight Brigade, with headquarters in the wooded Nepoui Valley, consisted of 29 Battalion, 1 Ruahine Battalion, the remaining units of 17 Field Regiment, 214 Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, 54 Anti-Tank Battery, 37 Field Park, 7 Field Ambulance with a field surgical unit and a 50-bed hospital, 4 Composite Company ASC, 64 Light Aid Detachment, and the Divisional Mobile Workshops. Row's task was the defence of the Plaine des Gaiacs aerodrome and the port of Nepoui. The southern sector was occupied by the smaller 15 Brigade, with the task of defending the road through the mountains from Houailou. Headquarters was established at Nemeara, with 1 Scottish Battalion in the neighbouring valley and 37 Battalion on the eastern side of the mountains beside the picturesque Houailou River. Attached were 23 Field Company Engineers, 29 Composite Company ASC, one company of 7 Field Ambulance, and 144 Light (3.7-inch) Howitzer Battery.

Dove, who was both Base Commandant and Officer in Charge of Administration, established his headquarters and some smaller units in the town of Bourail, with his major concentration of Base units in Racecourse Camp, in Tene Valley, and Boguen Valley, some miles away. Sub-base remained at Nouméa, 120 miles south over a dusty, pot-holed road. These dispositions were modified

six weeks later when 8 Brigade moved south to Bouloupari to take over a sector vacated by 43 American Division: 14 Brigade then extended its southern boundary to include Nepoui and the Plaine des Gaiacs aerodrome. Units remained in these sectors until the division moved from New Caledonia, holding three-quarters of the island. With the exception of those anti-aircraft batteries allotted to brigades, the heavy artillery was disposed in areas outside the divisional sector. The 33rd Heavy Regiment, under American command, shared the task of defending Nouméa Harbour with the 244 American Coast Artillery and a French battery. Its head-quarters were on Ile Nou, with one battery at Point Terre and its workshops in Vallee du Tir. The 28th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment had its headquarters and one battery and workshops at Oua Tom aerodrome and one troop of 204 Battery detached at Ile Nou; 29 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment was guarding the Plaine des Gaiacs aerodrome with the 208 Battery detached to 28 Regiment at Oua Tom.

In the mobile defence scheme brigades were given alternative roles for the mutual support of each other in the event of attack, and although more optimistic reports from the Solomons suggested that any danger to New Caledonia was becoming increasingly remote as the battle moved to New Georgia, alarm practices were regularly held on receipt of flash signals from Nouméa. These tested the signals link throughout the whole island and kept the forces reasonably alert, for there was still the possibility of hit-and-run raids by Japanese submarines which waited along the sea lanes between the Allied Pacific bases.

From the time of arrival, tented camp sites were established and made comfortable by that fantastic aptitude of the average New Zealander to make himself a home, providing he has a few boxes and nails with which to construct crazy but functional articles of furniture. Men lived in six-man Indian pattern tents, scattered irregularly among the trees and raised high off the ground by additional poles of the useful niaouli and bamboo to give plenty of head-room and air. The floors were sanded or metalled. Because of its usefulness the niaouli is worthy of mention. It covers vast areas of the dry side of New Caledonia and grows quickly. Its sparse, grey-green foliage resembles that of the Australian eucalypt, to which it is related, and its trunk is covered with thick bark made up of many layers each as fine and soft as tissue paper. The slender trunks are much used by the natives for constructing their huts, and the bark, which is dexterously stripped off without killing the tree, is used for roofing. The timber endures for long periods in the ground.

Despite the eloquent minority who found nothing attractive in New Caledonia until they left it behind them, the camps, though isolated, were excellent. Most of them were sited within easy reach of freshwater streams or rivers, so that bathing and laundering presented only those difficulties which could be overcome by the exercise of common sense. As the months went by mess rooms, offices, store-houses, YMCAs, and recreation centres were built in the fashion of large native bures to provide additional and more comfortable accommodation. These bures, also used by the French farmers, are constructed by roofing a skeleton framework of niaouli trunks with bark and reeds, held in place with strands of fibre from the aloe, plant, and covering the walls with sections of plaited coconut fronds. Native labourers, under engineer supervision, constructed the bures, and costs were met from unit funds. In each brigade area large recreational bures were erected and became the meeting place of all troops in the vicinity. Their most appreciative patrons were the transport drivers, who left the dusty roads for a few minutes to take a cup of tea during long journeys to and from the supply depots. By the time construction was finished some of the camps resembled native villages.

The rainy season brought problems such as the flooding of access roads, when they became bogs, and added to the worries of the engineers, who were so engulfed in maintenance work that units frequently went to their aid with their own transport. Rivers rose with astonishing rapidity, forcing the removal of some camps to higher ground and disrupting traffic on the main roads, but the mud soon gave way to dust as the year ebbed into the cooler season. Relations were never anything but cordial with the American forces, whose vocabulary, both official and unofficial, was adopted with limits. The French administrative officials, farmers, and store-keepers welcomed the New Zealanders, to whom they became a race of jolies garçons, with an enthusiasm which soon overcame all language difficulties. To the Americans they were never anything but ‘Kiwis’, since that bird had become the division's distinguishing mark and every vehicle carried one.

From the time of arrival in New Caledonia the division, by arrangement between governments, was maintained from American sources, with the exception of certain specified New Zealand supplies such as canteen stores, clothing, tentage and ammunition, though later American tropical clothing was also adopted. The men were paid in dollars, £2 worth of which had been changed during the voyage, but they also used French currency for local purchases and were soon busily engaged in attempting to reconcile the New Zealand pound at 6s. 1d. to the dollar with francs at 43 to the

dollar. Some of the American food was regarded with disfavour and the New Zealanders never became accustomed to spam, chile con carne, and others equally spiced, though they appreciated the fruits and juices and the liberal ration of turkey for such traditional festivals as Christmas Day and Thanksgiving Day. Quantities of fresh fruit, particularly oranges, and smaller amounts of fresh vegetables were purchased from French farmers to supplement and add variety to the daily tinned ration, but fresh butter and meat in reasonable supply did not become available until refrigeration storage space was increased in Nouméa. Refrigerated vans relieved the storage difficulties among units.

The pot-holed roads and the long distances over which supplies were hauled daily played havoc with transport, and many of the ASC trucks, which averaged 2000 miles a month, were soon bumped into the repair depots. Barrowclough, against the opinion of the Quartermaster-General, Brigadier H. E. Avery,9 requested full-scale transport of 3377 vehicles, which included 663 motor-cycles, 2016 cars, jeeps and trucks, and 507 tractors and carriers. By the end of June 2752 had been despatched from New Zealand. In an effort to make up the division's extensive deficiencies during its reorganisation, many of the trucks had been supplied from districts and were ill-conditioned for the harsh service required of them in New Caledonia. Thereafter Army ordered that only new vehicles be sent forward, some being obtained direct from American sources on the island. Because of pillaging, one of the nastier features of wartime shipping, all tools were removed from vehicles before they were shipped from New Zealand. Ultimately all transport reached New Caledonia, where much of it remained when the division moved into the forward area. Only one third of the division's transport was taken to Guadalcanal, and still less beyond that.

Barrowclough was continually worried by the deterioration of stores and equipment, which were inadequately housed, and by increasing problems of maintenance, which included the erection of reasonably permanent buildings and the upkeep of roads, now far beyond the limited resources and equipment of the French public works organisation. Although the division was better equipped than it had ever been in its history, shortages could not be met from American sources, which were often hard-pressed through losses at sea to meet their own requirements.

Some indication of the major difficulties was revealed in a report by Major L. C. Hardie, of Fortifications and Works Branch, Army

Headquarters, who spent from 21 March to 8 April thoroughly investigating the state of the division's services. ‘At present everything is of the makeshift, inefficient, and temporary type’, he noted in a long, detailed report, which included the state of the roads and camp sites. He observed that the provision of barges for use in unloading ships was largely the result of personal relationships and friendships existing between New Zealand and American officers, rather than any definite rights to use equipment as and when required. Although engineer supplies, under an original agreement, were the responsibility of the South Pacific Command, they were not available because the command itself was short. Hardie reported that the roads in New Caledonia were bad and road maintenance had broken down, building supplies were unobtainable locally, Base details camps were in great need of prefabricated buildings, and there was a distressing shortage of timber, water, drain and culvert pipes, pumping plants, power generating plants, water heaters, chlorinating and filtering plants, general hardware and cement. If New Caledonia was to become a base, many buildings of a permanent type were required for storage. This report hastened supplies from New Zealand, particularly a quantity of prefabricated buildings for the housing of ordnance supplies.

Some of the General's administrative problems had been revealed in his letter to Army Headquarters, written on 2 February:

‘I have to decide what should be the size of my Base installations and what degree of permanence my building construction should take. This is naturally bound up with the possibilities of our returning here and the number of reinforcements which are likely to be retained at Base. At the present time these problems are almost overwhelming. We have large stocks of rations which are deteriorating through exposure to the weather. The same applies to ammunition, and in both cases our problem is accentuated by the fact that large supplies of ammunition and rations were landed here at a time when I had few troops to handle them. Even now my numerous commitments are leaving only the barest minimum of training opportunities and I am handicapped largely by shortage of engineer equipment. Some roadmaking equipment has just arrived, including some bulldozers, only one of which is a D4 tractor equipped with earth-moving plant. Another D4 tractor is without this plant, two D7 tractors have no roadmaking fittings, and my CRE advises me that even if the materials could be sent over the workshops could not fit suitable earth-moving appliances. These tractors are practically useless, and in order to keep open access to my brigades I have to employ large numbers of men roadmaking with nothing but picks and shovels.’

The delay in sending forward equipment for the division was partly caused by shortage of shipping, but this was aggravated by the method of storage in wharf sheds in New Zealand and by a system of loading which did not ensure that cargo was shipped in

the order in which it was delivered. This prompted Dove, in a report on Base Headquarters organisation, to suggest that in any similar future operations a special ship should be provided so that shipments could be made in the desired order in which they were required. Any demand for shipping was made to the American authorities, but some confusion seems to have existed between the authorities, both American and New Zealand. The United States Navy, which was advised of 3 Division's requirements, had been shipping supplies only as space became available after its own requirements were satisfied. General Breene, of the South Pacific Command, considered that if he had been correctly informed of what had to be lifted both in reinforcements and supplies, he contemplated no difficulty, as he had other ships at his disposal which could be diverted. This ultimately solved the problem, though shipping space, during this period of the war, was always short in the Pacific, as elsewhere.

III: Life Among the Niaoulis

Everyone trained in New Caledonia. There was no option, since it was an instruction that all ranks of every branch and headquarters, even the less conspicuous elements such as cooks and batment, must undergo a fitness campaign and march certain distances. In a review of the state of training at the end of January, Barrowclough issued an instruction which included that: ‘It is essential that the whole division be trained in jungle warfare types of shooting. Artillery, signals, ASC, and ordnance must be trained with the rifle, Thompson sub-machine gun, and light machine gun to combat Japanese infiltration.’ He also suggested to Army Headquarters that the supply of grenades, which were ‘particularly suitable for jungle fighting because they did not locate the thrower’ be increased to 200,000. No time was lost in beginning a schedule of training for which the country is so perfectly suited, despite the mosquitoes, and where the soft warm nights are not attended with discomfort when sleeping out, though reconnaissance parties which explored tracks through the mountains rarely moved without their mosquito nets. These insects were at their worst in 8 Brigade areas in and around Bouloupari, where head-nets were often worn and office desks and signal equipments covered in an effort to overcome their agonising attentions.

Jungle training began on a platoon and company basis, using live ammunition, mortars and machine guns, over courses designed as a preliminary to manoeuvres on a larger scale employing battalions and finally brigades. Small parties made four- and six-day trips

through the mountains and along the beaches, investigating the state of routes, their availability for movement, checking supplies of food and water, and testing the value of certain specified rations over stated periods. Inaccurate maps gave little indication of the actual state of the country, but this only stimulated interest and encouraged initiative, for training in New Caledonia was never monotonous, despite its tests of stamina and endurance. As training progressed, every form of exercise was undertaken by battalions, from beach landings, using Higgins boats, to attacks on objectives over specially prepared tracts of country, using concealed targets and supporting arms. This went on for months, always with an eye to combat in the Solomons.

Some of the more spectacular exploits involved operations with American forces, such as an 8 Brigade exercise in February using 29 and 1 Scottish Battalions, which co-operated with elements of 43 US Division and United States aircraft. Another 8 Brigade exercise in April stressed communication problems in close country, the use of four-wheeled vehicles over tracks through the bush, and the reduction of the load carried by the individual soldier. Throughout May and June this brigade embarked on its most strenuous exercises, the first of which, from 4 to 7 May, took place over rugged bush and mountain country in the Ouenghi-Tontouta region with units divided into New Zealand and enemy forces. This was followed on 14 May by a still more exhausting exercise designed for the capture of a high hill feature, culminating in a five-day manoeuvre which involved carrying mortars and machine guns and other combat equipment up steep, bush-clad slopes and crossing rivers in assault boats and on floating rafts. Further exercises over long periods in June included attacks on La Foa and Moindou villages, for which sand models were used during discussions on problems and in lectures to the men to stimulate their interest, and for which they were invaluable. A recreational period at Thio, an attractive village on the east coast, was well earned by the whole brigade in the only respite it ever enjoyed from months of training.

In the dry, open country in the north, 14 Brigade had been equally busy, practising over an assault course, testing jungle rations during a beach landing on the Gomen Peninsula in April, and in defence and attack schemes which kept the units far from their camps. As a preliminary to the most thorough exercise undertaken by the brigade and involving all arms of the service, Divisional Headquarters held a tactical exercise without troops for brigade commanders, followed by another for unit commanders. Then, for three days and nights, all units of the brigade were employed in a night river crossing, followed by an attack on the village of

Pouembout. For this exercise the opposite bank of the Pouembout River was presumed to be in enemy hands, a bridgehead had to be established in darkness, and a force with anti-tank guns pushed over in readiness for the main attack next morning. Engineers used assault boats and box girder bridging to cross the river, the ambulance set up its hospital and treated several accidental injuries, signals tested the efficiency of communications, both line and radio, supporting artillery played its role, and the ASC fed and maintained the force. There were several visitors to witness this most realistic and exacting exercise, including two senior American generals, Harmon and Lincoln.

Fifteenth Brigade, while carrying out its various exercise, proved the value of its training during a three-day manoeuvre when not a man fell out. This brigade also tested the efficiency of various rations, and came to the conclusion that some of them would do little more than sustain men in action, leaving them no reserve for fighting. One of these was the American K ration, which was neatly enclosed in a cardboard package for easy carriage and contained ¼ lb. of cheese or meat in an airtight tin, eight small biscuits wrapped in cellophane, sixteen glucose tablets, three lumps of loaf sugar, powdered fruit juice for two drinks, one stick of chewing gum, and one carton of four cigarettes. Other similar rations contained soup cubes. These were all designed for use during assault landings, each man carrying three packages made up as three separate meals, and sufficient to last him for 24 hours. All of them were disliked after the novelty wore off, but they were efficient for their purpose.

Through May and June, also, the men were toughened by arduous marches, 8 Brigade beginning with 14 miles a day, increasing to 18 and finally to 40 miles over the last two days. Units of 14 Brigade marched 20 miles a day for three days, culminating in an ambitious military display in which every unit played a part, and ending during the weekend with a church parade and ceremonial march past. Later in July, 8 Brigade held a ceremonial parade and review during the visit of the Minister of Defence, the Hon. F. Jones, who inspected the men.

Although taking part in the various brigade exercises, other arms of the service continued their individual training, in spite of the distracting calls on their time for routine duty. When anti-aircraft artillery units could not obtain the assistance of aircraft for trail shoots, they improvised by using kites or balloons towed by jeeps; engineers experimented in floating jeeps across rivers, using kapok assault floats or tarpaulins, and in building bridges at night, using materials cut from the nearby bush; signals had practice enough in

their work, which called for the erection and maintenance of miles of line through the roughest country, and the servicing of a radio net which extended from Nouméa to Taom and a high-powered link sited at Base, which carried all traffic between the division and New Zealand.

Unlike other divisions in the field, 3 Division, the only formation other than American then in the South Pacific, was without the usual Army Corps organisation on which it ordinarily would have called. This meant that Army Headquarters and the South Pacific Command to some extent took the place of the larger formation. Its training, also, was entirely different from that laid down in the manuals, in which emphasis is placed on traditional methods used in open country such as the European mainland or the African desert.

New Zealanders of 3 Division, for the first time in history preparing for jungle and island warfare, were practically writing their own text books as their training progressed. All the months of works accomplished in New Caledonia were of immense value, and during that time the division experimented for future operations, adding to its ideas and equipment and discarding what was unnecessary. Long trousers and long-sleeved shirts were necessary because of mosquitoes; steel helmets were useless among trees and undergrowth because of the noise; gas respirators proved a hindrance in wooded country; canvas boots with barred rubber soles were superior to leather footwear in the jungle; some reduction in the amount of personal gear was essential. ‘Streamlining in the jungle is not merely a desirable appearance but is a military necessity,’ one unit reported. ‘A water-bottle and haversack hung on the sides of each soldier may well represent so many coffin nails.’ Tea proved to be the greatest stimulant for fatigued men and rice a popular food, though difficult to cook because water was often short. Troops soon tried of the American jungle rations, compact and efficient though they were.

Throughout the training period specially selected officers and men were despatched far and wide to gather the latest information on jungle fighting and amphibious warfare. Some went to amphibious training courses in the United States, returning rather too late to be of any assistance in the Solomons; others were sent to chemical warfare schools in Australia, Army School at Trentham, the AFV school of Waiouru, the tactical school at Wanganui, and staff college at Palmerston North.

Training culminated at the end of June with amphibious exercises using an American ship, the John Penn, off the beach of Ducos Peninsula in Nouméa Harbour. Here a combat team of 1139 all